This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The turmoil on college campuses and at the Democratic National Convention in 1968 helped propel Richard Nixon to victory—and marked the long-term transformation of national politics. Donald Trump is likely hoping that history will repeat itself.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Here We Are Again

I remember the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago because I was there. My father was a delegate. I was a page. And I stole the Wisconsin delegation’s sign.

How could I forget? I was 13 years old and found myself watching police assault rioters in the streets. In the convention hall, where, amid the political chaos, I ran around delivering messages among the delegations, I had a front-row seat to a political party tearing itself apart.

Although the convention that year ended up nominating the amiable vice president, Hubert Humphrey, for the presidency, the indelible images from Chicago were scenes of police brutality, and of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley screaming at a Jewish senator from Connecticut, Abe Ribicoff, after Ribicoff took to the convention podium to denounce what he called the “gestapo” tactics of the police attacking anti–Vietnam War protesters.

My father, Jay, who had been the Wisconsin director for Eugene McCarthy’s anti-war campaign, later described the Chicago convention as trying to hold “a Rotary Club luncheon in the middle of World War I.” Because McCarthy won the Wisconsin presidential primary, his supporters controlled the state’s delegation, which was at the center of much of the convention’s drama—at one point McCarthy’s supporters even put a young Black state representative from Georgia named Julian Bond into nomination for vice president.

I knew the convention was something I wanted to remember, so on the last day I ran across the convention floor and grabbed the tricornered Wisconsin pole and managed to get it all the way home, where it sat for years in our garage as an artifact of that extraordinary, pivotal moment.

Despite the inevitable comparisons, it’s unlikely that the return of the Democratic convention to Chicago this summer will have anything like the Sturm und Drang of 1968’s violent fiasco. This time around, Democrats are behaving like a more or less unified political party, and threats by protesters to disrupt this convention may not amount to much, David Frum noted this week, because the police have learned their lessons. And, he points out, although college campuses have recently “been distinguished by more rule-breaking than the convention protests of the past two cycles … pro-Palestinian protests on this side of the Atlantic have generally deferred to lawful authority.”

But the parallels between 2024 and 1968 are ominous, especially as protests spread across university campuses like they did back then. The turmoil of ’68 not only helped propel Richard Nixon to victory in November but also marked the long-term transformation of national politics. The images of disorder on campuses and in the streets helped break the New Deal coalition apart and drive conservative and centrist voters away from the Democratic Party; they hastened the realignment of much of the American electorate. Republicans would hold the White House for 16 of the next 20 years. Indeed, the politics of the past six decades have been shaped by the divisions that sharpened that year. In 2024, we are still suffering from the hangover of 1968.

And a particular risk has emerged from the campus chaos of today: Even as the nation faces the clear and present danger of right-wing illiberalism, the next few months could be dominated by the far less existential threat of left-wing activists cosplaying their version of 1968. Tuesday night’s dramatic police action to clear an administration building at Columbia University that had been seized by anti-Israel activists took place 56 years to the day from one of the most violent clashes between police and protesters on that same campus. In 1968, activists occupied half a dozen university buildings during protests against the university’s affiliation with military research and its plans to build a segregated gym in a predominantly Black neighborhood. That occupation ended violently after New York police officers clashed with protesters and cleared the buildings. Hundreds of students were arrested, dozens injured, and an NYPD officer was left permanently disabled.

A “fact-finding commission” headed by the future Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox found that “the revolt enjoyed both wide and deep support among the students and junior faculty.” But the protests generated a backlash from the American public. The political fallout from 1968—a year that saw riots in cities, assassinations, campus upheavals, and the DNC riots—was immensely consequential. In 1968, both Nixon and Alabama Governor George Wallace (who was running as a third-party candidate) made the disorder in the streets and on campuses the centerpiece of their campaigns. In November, the two men received a combined 56.2 percent of the popular vote—just four years after Lyndon Johnson’s Democratic landslide over Barry Goldwater.

But many campus activists, who were beginning the decades-long project of romanticizing 1968, felt emboldened. In 1970, after the killing of four anti-war student demonstrators by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University, protesters across the country tried to shut down universities, including the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, where my father taught journalism. Despite his opposition to the Vietnam War—and his role supporting McCarthy’s insurgent anti-war candidacy—he was appalled by the tactics of the protesters who occupied the university library, leading to its closure, which my father regarded as “a new version of book burning,” according to his unpublished manuscript. A Jewish World War II veteran, he refused to shut down his classes, and when he ordered occupiers to leave the office of the student newspaper, he wrote, he was denounced as a “fascist pig.”

Two years later, in 1972, despite the brewing Watergate scandal, Nixon won reelection with 60.7 percent of the popular vote and 520 electoral votes.

And here we are again. Now, George Packer wrote in The Atlantic, elite colleges are reaping what they have been sowing for decades. This month’s turmoil on campuses like Columbia’s “brings a strong sense of déjà vu: the chants, the teach-ins, the nonnegotiable demands, the self-conscious building of separate communities, the revolutionary costumes, the embrace of oppressed identities by elite students, the tactic of escalating to incite a reaction that mobilizes a critical mass of students.”

Donald Trump obviously hopes that history will repeat itself, and that the left-wing theatrics of the anti-Israel protests, on college campuses and beyond, will have an outsize effect on the 2024 election. Like Nixon and Wallace before him, Trump (and the congressional GOP) will seize on the protests’ methodology and rhetoric—this time to further polarize an already deeply polarized electorate. The irony, of course, is rich: Even as Trump stands trial for multiple felonies, he is trying to cast himself as the candidate of law and order. Even as he lashes out about the campus protesters, he is pledging pardons for the rioters who attacked the Capitol.

But Trump would be right to think that every banner calling for “intifada,” every chant of “From the river to the sea,” every random protester who shouts “Death to America,” and every attempt to turn this year’s DNC into a repeat of 1968 brings him closer to a return to the Oval Office.

Related:

Today’s News

- During a visit to Israel, Secretary of State Antony Blinken pressed Hamas’s leaders to accept the current hostage deal, which calls for Hamas to release 33 hostages (down from the 40 that Israel had previously requested) in exchange for a temporary cease-fire and the deliverance of many Palestinian prisoners.

- House Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene announced that she will try to oust House Speaker Mike Johnson from his role next week.

- Democrats in the Arizona Senate pushed through a repeal of the controversial Civil War–era abortion ban that allowed only abortions to save the patient’s life and had no exceptions for rape or incest.

Evening Read

The Mysteries of Plant ‘Intelligence’

By Zoë Schlanger

On a freezing day in December 2021, I arrived in Madison, Wisconsin, to visit Simon Gilroy’s lab. In one room of the lab sat a flat of young tobacco and Arabidopsis plants, each imbued with fluorescent proteins derived from jellyfish.

Researchers led me into a small microscope room. One of them turned off the lights, and another handed me a pair of tweezers that had been dipped in a solution of glutamate—one of the most important neurotransmitters in our brains and, research has recently found, one that boosts plants’ signals too. “Be sure to cross the midrib,” Jessica Cisneros Fernandez, then a molecular biologist on Gilroy’s team, told me … Injure the vein, and the pulse will move all over the plant in a wave. I pinched hard.

On a screen attached to the microscope, I watched the plant light up, its veins blazing like a neon sign. As the green glow moved from the wound site outward in a fluorescent ripple, I was reminded of the branching pattern of human nerves. The plant was becoming aware, in its own way, of my touch.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

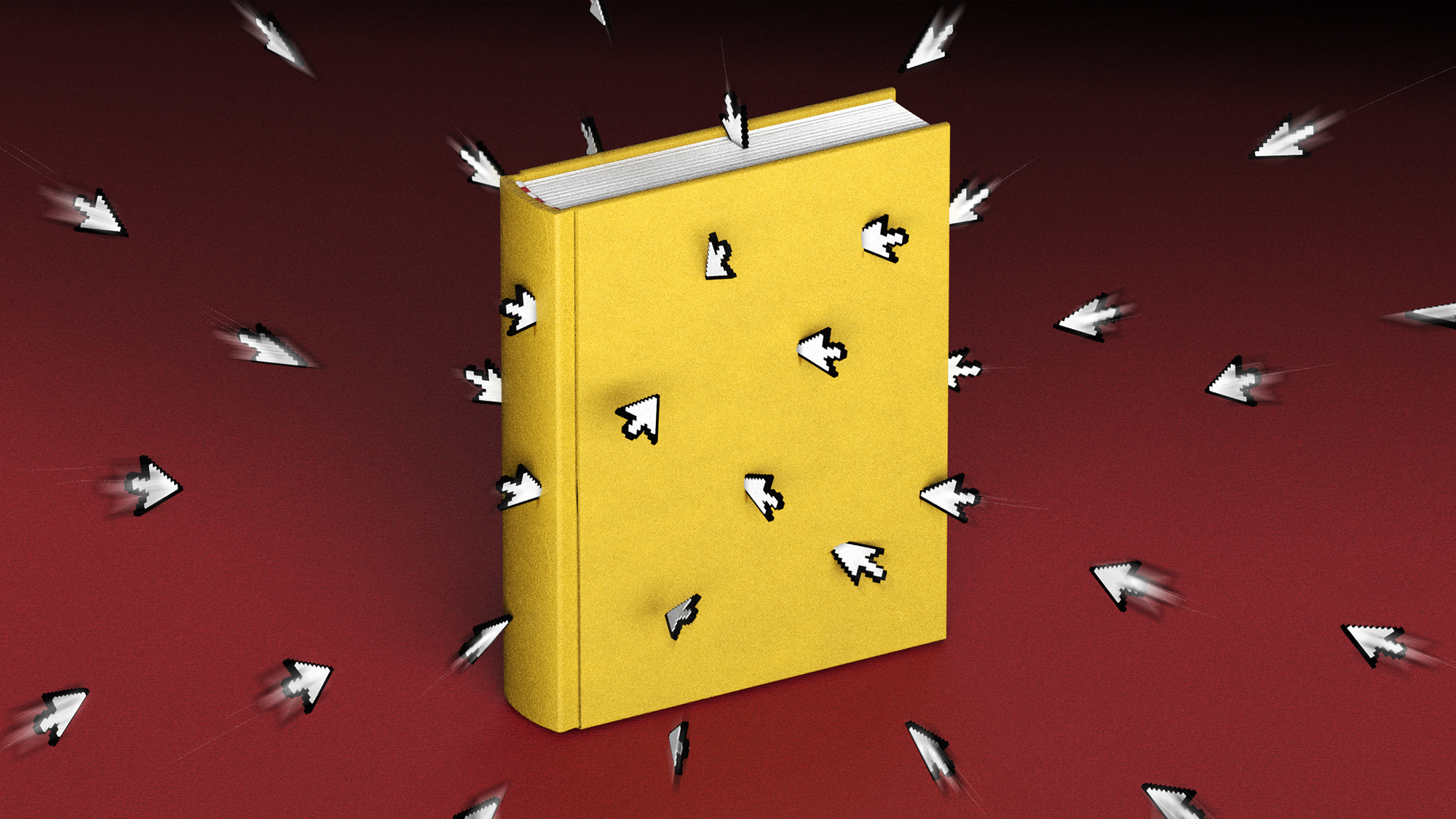

Discover your taste. The internet makes most information instantly available, W. David Marx writes. What if that’s why mass culture is so boring?

Read. In the 1950s, Paul Linebarger, a psyops officer and sci-fi writer, wrote stories about mind control and techno-authoritarianism that underpin our modern conspiracy theories, Annalee Newitz writes.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.