Streatham, South London, the birthplace of a trailblazer in popular culture, Naomi Campbell. Nearby, along Streatham High Road, among an eclectic mixture of shops in mid-terrace houses, you reach De Ver Cycles, run by a trailblazer in British cycling, Maurice Burton.

On this spring Saturday afternoon, Burton is busy giving advice to a couple of young men interested in buying a road bike. Soon, a young woman comes in wanting to bag the last gravel bike available in the sales.

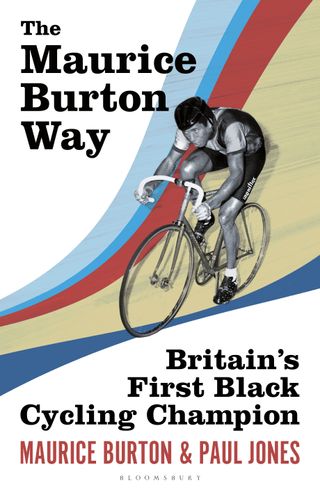

The shop is buzzing with activity as others come in to drop off their bikes with the mechanic. A few also buy a copy of his newly released autobiography – The Maurice Burton Way – Britain’s First Black Cycling Champion.

“I hadn’t set out to write a book, but I hope that this could be an inspiration to young people and a way to show it can be done,” says the 68-year-old who has run his shop since he acquired it in the late eighties.

For all his success, Burton is pretty modest about his achievements. Hanging above the counter is a photo of his shop in its original form when he bought it from Peter Verleysdonk, a friend and professional cycle racer, in 1987. The former British track cycle racing champion had used all his savings from his racing days and what he’d earned as a cycle courier after his professional cycling career ended abruptly. Initially, Burton sold mainly leisure and second-hand bikes from his single-fronted shop. Thanks to his business acumen, partly instilled into him by his father, Rennal, and partly from the cut-throat business of Six-Day racing, he purchased the adjoining houses. De Ver Cycles is now a triple-fronted outfit, selling a wide range of brands, including high-end road, gravel bikes and folding bikes.

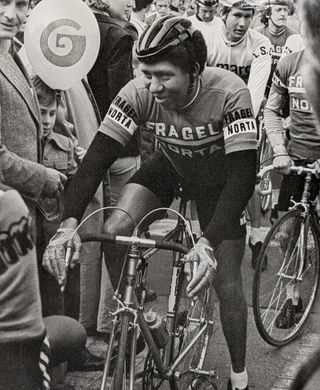

Dotted around the shop’s walls are many photos from Burton’s racing days, which hark back to the heady days when Burton was a travelling professional racer on the gruelling Six-Day track racing circuit around Europe and beyond during the 1970s and 80s. This success came on the back of a difficult period as a UK-based rider—often because of his race.

In the UK, Burton had come to prominence in the early- and mid-70s when he scored big wins at the Good Friday Track Cycling Meeting at the historic Herne Hill velodrome in South London. At barely 20 years of age, the mixed heritage British Jamaican won the ironically named White Hope Sprint race in 1974, and the Golden Wheel points race, which included a sprint every lap. In doing this Burton had bettered some of the strongest British track cyclists in those days. Thanks to the young Londoner’s coach and founder of the successful Velo Club de Londres, Bill Dodds, plus British Cycling Federation coach, Norman Shiels, who were very encouraging towards the 19-year-old, Burton competed in the Commonwealth Games in New Zealand.

He also won National Track Cycling Championships as a junior, and as a senior, notably the 20km Scratch Race at Leicester in 1974. Sadly, what should have been a great moment for the rider was memorable for the wrong reasons. During the race, a couple of fancied riders like Steve Heffernan, Chris Cooke and Mick Bennett crashed out, and Burton powered on to win. However, neither the media nor the crowd really acknowledged the youngster’s achievement. In fact, the crowd booed as Burton took the top step of the podium.

Burton received a complimentary invite, along with a group of other international riders like Niels Fredborg, John Nicholson and Daniel Morelon, to race in a series of races in Trinidad and Barbados in 1975. However, British Cycling instructed him not to wear a Team GB jersey as it was not a racing series endorsed by them. A starry-eyed Burton then boarded the plane as a free agent wearing his National Champion’s jersey and met with these top names in world track cycling.

Despite being a quicker rider than his fellow Team GB competitors, Burton was not selected to represent his country at the Montreal Olympics. While Norman Shiel had been very positive about Burton’s abilities, the selectors, Tom Pinnington and Bob Bicknell, had other ideas, and did not see much beyond the youngster’s skin colour. Burton needed to find a way to advance his career.

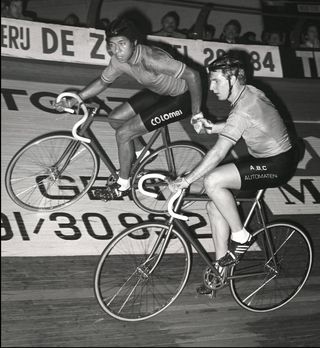

One of Burton’s proudest moments would be when he raced against Eddy Merckx in Ghent. That evening, with his partner Paul Medhurst they had beaten Merckx and his partner Patrick Sercu at a Madison elimination race. Later that evening, in the individual elimination race, Burton and Merckx were up against each other as the final riders left. In front of the roaring, partisan crowd, where Burton had been ahead of the Belgian champion, Merckx drew level with the young Brit and said in a low voice, “You let me win this one?” Burton obliged, dropping back to let the Cannibal have the victory. To this day, Burton describes this moment as a great honour.

For Burton, Merckx was not just a great racer but also the person who inspired him to get into cycle racing as a schoolboy in Catford, South London.

“He’s the only one I knew about because I saw him on the television on World of Sport, with Dickie Davis. They used to show about 10 minutes of the Tour de France – just 10 minutes on black and white television. It was in 1969 and I remember seeing Eddie winning. My dad was there, and I said to him, ‘I want to be like him,’ and my dad said, ‘You’ll have to eat steak every day if you want to ride like him’.

Interestingly, Burton, as a young Black boy in South London, was inspired to get into cycling after seeing a white Belgian man racing in France. That certainly goes against the mantra of “You can’t be what you can’t see.” When I asked Burton about this, he hadn’t heard of such a saying.

“I went to school, and I rode at Herne Hill with Joe Clovis – this was in 1972. Then I said to Joe, ‘We need to find out what it’s like to ride on a steep track. I’ve never ridden on a steep track.’ In my mind, I think that if somebody else can do it, so can I. I don’t care what colour they are! If you are going to say, ‘Because they don’t look like me, I don’t think I can do that,’ isn’t that some sort of insecurity? I see it like this: if they’ve got two hands like me, they’ve got two feet like me. Have they got something that I haven’t got, or vice versa? No. So if they can do it, why can’t I? I think a lot of people put a barrier in front of themselves to convince themselves that they can’t. But ‘can’t’ doesn’t come into my vocabulary.”

Although Burton is very driven he still acknowledges that there are difficulties for people who are different, though he is also motivated by a strong self-belief.

“If you have to get through a door to be where you want to be, there are two ways you can do it. The easiest way is to go straight through it. For some people – people like me, it’s not always possible to go straight through. Sometimes, you have to take a longer route round, but you can still arrive at that destination if you want to.”

Like many Black parents, Burton’s father had hoped for him to follow a more professional path – become a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer – rather than being an athlete. But Burton knew what he wanted to do in life.

Burton recalls: “With my friend Dexter, we’d go out for the day. By the time I was 12, and he was 10, and I’d got my bike, we’d meet on Blackfriars Bridge and go off riding – to Kew Gardens or Chessington. I’d tell my parents I was going out, but they didn’t know what we were doing. I may have been going to a race, but they didn’t know. I just did it!” It wasn’t until after Burton became junior National Champion that his parents first saw him race.

“For some people – people like me, it’s not always possible to go straight through. Sometimes, you have to take a longer route round, but you can still arrive at that destination if you want to.”

Despite the passing of the Race Discrimination Act in 1968, racism in Britain was still rife, and this was apparent in the way he was shunned by some of the officials at British Cycling. Racist remarks were commonplace in everyday life.

Burton says, “Things are different now, but at school, people used to look at you and think, ‘What are you doing here?’”. He also recalls vividly the use of racial slurs and offensive remarks while at school.

On the wall of the office in Burton’s shop, a card with a poem is taped to it. The words of the poem, ‘If’ by Rudyard Kipling, have been a very helpful mantra by which the former Champion lives his life. Such words as: ‘….If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, But make allowance for their doubting too….’ gives a lot of meaning.

“I am a religious person to a certain degree,” Burton explains, “I’ve never read the Bible from cover to cover, but this poem is a condensed guide to life, and I think if you follow that, I don’t think you can go too far wrong.”

Amid the stagnant and, at times, hostile environment in the UK, Burton figured that reaching his goal of becoming a professional cycle racer lay in taking the first part of his circuitous route – racing in Belgium. On a cold Christmas night and after a crash course in learning to drive from his friend John Nicholson, they set off for Ghent.

Burton gave himself a mini monetary goal as a way to see if this was the right move for him. He explains: “I went there with a bike and £100. It’s a simple way to find out if you’re good enough. In the summer, there were races and you could race nearly every day within an hour’s ride of Ghent. It would cost you around 20p to enter a race in Belgium, and there are 20 prizes. If you finished in the first 5 or 10 riders, you’d earn enough to live on, even as an amateur. So if you ran out of money, you’d get your answer! Maybe it’s best to look for a different job!”

However, Burton makes no bones of the fact that it was a hard life. Six-day racing was a relentless way of making a living. Riders would be competing every day constantly for six days in velodromes across Europe and beyond, racing until the early hours of the morning, entertaining capacity crowds that were cheering, jeering, shouting, drunk, and smoking heavily. You had to race in that smoky, cold, sometimes literally freezing environment. One velodrome in Zurich was built on top of an ice rink. It wasn’t uncommon for riders to race on just a couple of hours of sleep, having travelled for 12 hours, or even racing with a chesty cough or cold.

As for the actual racing, it was a dog-eat-dog world, where covert negotiations would take place with promoters for riders to be able to race on the lucrative Six-Day circuit, and some riders would receive a “cadeau” – being put in an easy pool of riders to assure a win.

Burton was particularly appreciative of Oscar Daemers, the promoter of the Ghent Six-Day races, who spotted his talent and got the young, newly arrived rider into events he was promoting.

“You had to watch your back at all times because the money was big,” Burton recalls. “After my first two Six Days, with the money I earned, I could go out and buy a brand new Toyota Celica. Where else was I going to earn that kind of money? I hadn’t finished my apprenticeship as an electrician, so I couldn’t do that.

“Most tracks could only accommodate 24 riders. On the bigger tracks of 250m, you could get 36 riders on there, but that was it. There must have been 250 riders or more to choose from. So promoters could easily find somebody else if one person didn’t perform. Everyone was watching their backs because no one wanted to lose their place. Sometimes you were happy if you were successful, but it was a hard job; it’s just what we did.”

At times, Burton’s bike was even tampered with, such as the cranks being tightened to make it hard for him to pedal fast. Such was the problem that his soigneur took to sleeping next to the bike and guarding it. Sadly, it was this tampering in 1984 that Burton attributes to his career-ending crash in Buenos Aires in which he broke his femur.

Although Burton enjoyed more success overseas than he otherwise would have done in Britain, the ugly face of racism still reared its head, particularly in the amateur ranks and from the English-speaking riders.

Burton recalls name-calling, in particular, from two Australian brothers – Peter and Jeff Delongville. He ignored them and put it down to jealousy, but one particular instant caused Burton to react. He recounts the story:

“At a race in Ghent, they tried to ride me over the rail. Do you know what happened to the last guy that went over the rail at Ghent? It was a Spanish guy, Isaac Galvez. He died. Well, they tried to put me over that rail. So after the race, I went to Jeff’s cabin where he was having a massage, and I turned him off the table, wrecked the place, and gave him a good hiding. I got a two-month suspension for it. His brother Peter came looking for me one night while drunk, saying he was ‘looking for the Black man so he could beat him up.’ So I came out to him. We fought, and I kicked him down the stairs.”

When he looks back at those racist incidents, Burton smiles. He managed to turn professional where many didn’t, and he feels content with what he has achieved in his life.

As well as being a British track cycling champion at junior and senior level, and competing in the Commonwealth Games, Burton competed in 56 professional Six-Day races. British Cycling has redressed their failure to recognise his achievements by inducting him into the British Cycling Hall of Fame in 2023. He also has a cycle path (Cycle Superhighway 7) that runs from South London to the City of London named after him, Maurice Burton Way.

“Cycling has given me a lot of things. It made me feel that I could do something well, and that gave me confidence. There were a few people like Bill Dodds, Norman Shiel and Oscar Daemers, who saw my potential, gave me the opportunity, and it made me feel wanted. Doing the tough Six-Day circuit also taught me a lot of life lessons that I still use now, in the tough world of business too.”

Burton sees cycling as an activity that could benefit youngsters.

“I think British Cycling could work more with youngsters in the inner cities – especially London, where they have all this knife crime going on. If you can get them away from that environment and bring them into cycling and maybe let them know, that if they do well, they could go on a trip to Amsterdam or Berlin or somewhere to ride. When I was a junior, in my last year at school, Norman Shiel sent me to the National Training Centre at Lilleshall, and the school gave me £10 from the Parents Teachers Association. £10 was worth a bit more than it is now. Then I went to Munich to race. I’d never been on an aeroplane before. The second time I was on an aeroplane, they flew me to New Zealand. If you let a youngster know they could go away like that they’ll feel good about themselves. Then they’re less likely to do these other things,” he says.

“I feel I have achieved what I wanted in life. I’m in a situation where I can look after my family. I’ve been able to buy myself a Bentley. If I want to buy an aeroplane ticket, and go to Australia, I can do that. I don’t need to take over the world. I don’t want to have a hundred shops – I’m happy with one shop as long as I can have the quality of life I want. That’s it.”

The Maurice Burton Way: Britain’s first Black Cycling Champion by Maurice Burton and Paul Jones (Bloomsbury Sport) is available to buy in hardback now.