Book Review: Thanks to “Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia” by British author/Italian resident Herbie Sykes we have not only an English-language history of the Giro d’Italia, which is in itself distressingly rare, but an extraordinarily entertaining book.

Published by Rouleur in 2011, this is not an inexpensive book and my first thought on pulling my limited- edition volume out of its slipcase was that it is not very large. But at over 300 pages of quite dense type and featuring a marvellous collection of photos, it is actually quite exhaustive in detail but reads like a thriller that draws you in further and further.

Bike racing had begun in Italy in 1870 and as Italy, a nation of peasant-farmers, began to transform into an industrialized country, although at a very unequal rate as the northwest enjoyed rapid economic growth while the south, which suffered massive immigration to other countries at the same time, remained mired in poverty. Literacy was at 52%. Milan, representing the wealthier part of the country, was a hotbed of cycling and new events sprang up rapidly. Nobody had quite worked out the format yet so there were oddities such as the King’s Cup, a 500 km one day race, in Tuscany, or the 15 hour Tour of Piedmont. The stage was set for Milan-San Remo, which began as a disastrous car rally but was turned into a bike race instead, sponsored by the Gazzetta dello Sport newspaper, which also managed the new Giro di Lombardia race. From these promising beginnings (rife as they were with cheating, fan violence and indestructible racers), in 1909 it was decided by the Gazzetta’s managers that a stage race in imitation of the Tour de France would sell lots of newspapers and the Giro was born.

Frankly, much of what Mr. Sykes has written about the early days of the Giro is so ridiculous you would think it is actually fiction. And this is what makes the Giro d’Italia so attractive. In its long history it has been unpredictable, exciting, confusing, sometimes unfair and often astonishingly disorganized. It has turned up a cast of extraordinary characters, including, along with established stars, all those unemployed and hungry riders in that first race who, Mr. Sykes assures us, had borrowed bikes in the hope of earning enough to feed themselves and their families for a while, a stage win providing enough for several months’ worth of meals.

The roster of extraordinary characters is overwhelming as the author paints exceptional brief portraits of riders with nicknames like the Red Devil, the Squirrel, the Human Locomotive and the King of Mud. Tano Belloni, who went from Greco-Roman wrestling to compete with the first Campionissimo, his friend Costante Girardengo (the latter winning the longest stage of the Giro ever, 430 kms, in a sprint finish in 1914). Belloni, winner of the brutal 1920 Giro but who was most proud of having taught himself English, became a celebrated Six Day racer and rode the track until he retired at 42.

The book is a fascinating mass of these details, with each chapter generally focused on a specific and always larger-than-life character. To some extent the Giro has always been more Italian in nature than the Tour de France, with its international aspirations, was French. In a nation so recently pieced-together, the race was a way of reinforcing political unification through sports (spectacle might be a better description). Italy was still a patchwork work-in-progress, and Mr. Sykes, who entertains with some personal commentary, has this to say about the Canavese, who live in a sub-Alpine region of Piedmont and produced a stream of exceptional riders in the 1920s and 30s:

“When spoken eloquently their dialect resembles an utterly indecipherable mouthful of toffee-chewing French, whistling northern Italian and, overwhelmingly, what’s best described as a kind of Neolithic grunting. Uniquely as far as I am aware in Western Europe, it contains no discernable vowel sounds whatsoever.”

This was no handicap for Giovanni ‘Giuanin’ Brunero, three-time winner of the Giro, and winner of Milan-San Remo and Lombardy, among other victories, who was a sensational climber and well-liked in the peloton. He is almost forgotten today even by the Italians and Mr. Sykes’ comments about this rider, who had a difficult life marked by family tragedy coupled with his own early death at 39 due to tuberculosis, are sympathetic and welcome.

Brunero.

Following demands by the riders that they get paid for participating, the Gazzetta tried to control expenses by not allowing trade teams to compete in 1924, promising food (again, food!) to riders who would sign up, finding 90 hungry amateur participants. Among them was a 32 year old woman, Alfonsina Strada, who guaranteed massive interest in the race. Although the author describes her as ‘a serial crasher’ and she was eliminated on a time cut, the organizers paid her to continue and a woman thus ended up being the top earner in the Giro d’Italia that year, completing the 3,600 km long race, one of only 30 riders to do so.

Just when you think the Giro cannot get stranger, it does. The great Alfredo Binda was just too good so the organizers persuaded him that just maybe he should go ride the Tour de France instead of the Giro, which he had effortlessly dominated. Which he did, given enough money!

Ponzin.

1931 saw the introduction of the Maglia Rosa, again in imitation of the Tour de France’s leader’s jersey. The winner that year was a young climber, Francesco Camusso, nicknamed ‘the Chamois of Cumiana.’ Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was not enthusiastic about the jersey colour, which he deemed ‘effeminate’, but the race, in which the favourites crashed out, turned out to be a classic battle. And over the years there have been more than a few at the Giro. Legendary was the rivalry between Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali, well-documented in cycling history. But so much of what the author writes is half-forgotten, and I defy anyone to read his account of the short, terrible career of Orfeo Ponzin, son of destitute farmers, without being moved.

A strong, shy young man of 20, he had watched his younger brother Armando take up racing. In the spring of 1950, Armando taught him how to ride a bike and was astonished at Orfeo’s natural talent. Within three months Orfeo, who had “not the faintest idea how to ride in a group, how to follow a wheel, how to handle his bike or descend safely, was a shoo-in for a pro contract, for a way out of serfdom.” But in the end it turned out very badly and poor Orfeo became one of that unfortunate band of riders to die racing, fracturing his skull from falling after hitting one of the concrete blocks lining the asphalt of the road during the 1952 Giro. And as this year’s Giro sadly reminded us, racing is still more dangerous than we often think.

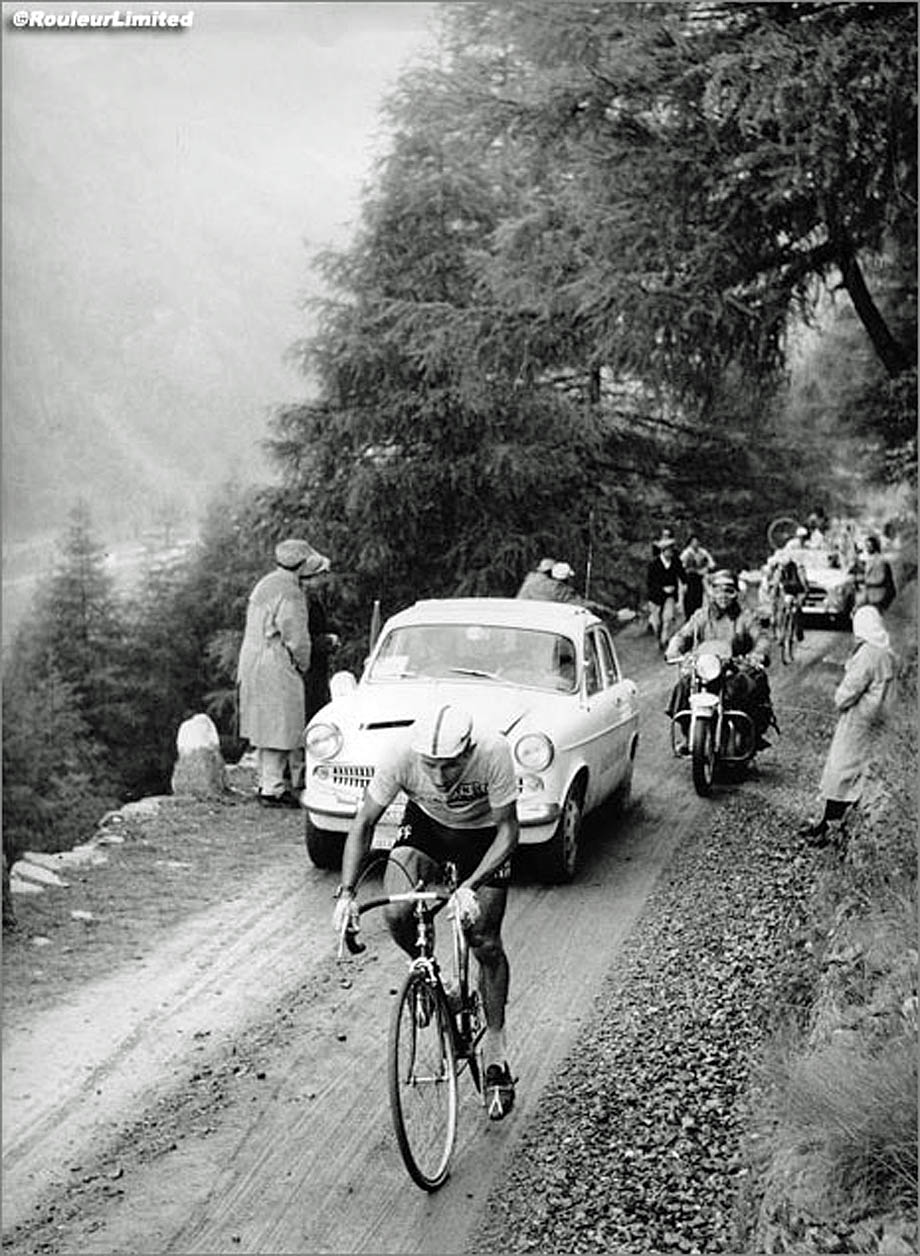

Anquetil on the Gavia.

There was a golden post-war period at the Giro. Along with Coppi, victories came to great names including Fiorenzo Magni, Hugo Koblet, Charly Gaul and Jacques Anquetil. Moving into the modern era, the Giro found itself stumbling forward. “Though beautiful, dynamic and unpredictable, organisationally it always gave the impression of having been slightly cobbled together, principally, because, quite frankly, it was.” By 1980 the race, unlike the successful, slick, brilliantly-marketed Tour de France, was essentially bankrupt. But it was revived by the brilliant wins of Bernard Hinault (three times entered, three times victorious) and the exciting rivalry of Francesco Moser and Giuseppe Saronni. The advent of Eddy Merckx in 1968 saw a long period of foreign domination, with only occasional Italian wins. Since 1997, however, Denis Menchov and Alberto Contador are the only non-Italians to have won the race.

The Giro is not without its problems, often seen as an also-ran to the Tour de France. The author vehemently condemns the thinking behind the centenary Giro d’Italia in 2009, which featured a disappointing parcours that ignored many of the celebrated places of Giro history, angering the tifosi. Italian cycling has been going through a lengthy crisis as it struggles to deal with the issue of doping and Italian to find successes on the road, which have become less frequent. In 2024 there is no World Tour-level team registered in the country, although there are currently 63 Italian cyclists riding at the top level.

Coletto.

Mr. Sykes certainly speaks with his own voice and in addition to his intriguing ruminations, the book features superb photos, generally black-and-white and, benefiting the subject, often very dramatic. “Maglia Rosa” is an enormous pleasure to read, and often made me realize why there are so many things to love about the disorderly, messy, crazy Giro as it stumbles its way around one of the most beautiful, and passionate, places on earth. Sure, we can all wax eloquently about the philosophy of bike racing, but it has its farcical elements that Mr. Sykes clearly cherishes.

Dancelli 81, Gimondi 107, Zilioli 32, Merckx 1.

“When Morgagni politely enquired how he (Ganna, winner of the first Giro) felt after such a breathtaking feat of endurance he replied, in broad Milanese dialect, that ‘Me brьse el cь’–‘I’ve got a sore arse’…”

The 2nd edition of the “Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia,” although published 13 years ago, is readily available both in softcover and hardback versions from Amazon.com or through Abebooks.com or E-Bay.

A Limited Edition of 120 books was available signed by former 14 Giro riders, who accounted for 17 overall Giro victories and over 80 stage wins but rapidly sold out. Oddly enough, the book is not signed by Andy Hampsten, the only American winner, who wrote the Foreward!

2nd Edition “Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia”

by Herbie Sykes

$39.93

309 pp., Rouleur Limited, 2011

ISBN 978-0-9564233-5-1

• Buy “Maglia Rosa: Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia” on AMAZON.COM.