Nothing ruins a perfectly good runner like plantar fasciitis, the dreaded snake bite of the heel and arch of the foot. In essence, it’s nasty foot pain — particularly heel pain — that prevents us from running. Once it sets in, is one of the most menacing and stubborn conditions.

Nothing ruins a perfectly good runner like plantar fasciitis, the dreaded snake bite of the heel and arch of the foot. In essence, it’s nasty foot pain — particularly heel pain — that prevents us from running. Once it sets in, is one of the most menacing and stubborn conditions.

Ultrarunners seem particularly prone to heel and arch pain. Both uphill and downhill running stresses the foot: the ups stressing the soft tissues of the plantar arch, and the downhills providing ample pounding for the joints.

It’s okay to call your foot and heel pain plantar fasciitis — just like that Coke at the aid station that might be Pepsi or RC Cola. But be sure that you — and your doctor, PT, chiropractor, LMT or other healthcare helpers — are aware of all of the different sources of foot pain. Awareness is the first step in comprehensive treatment and fast recovery from the dreaded “PF” and its brethren.

Plantar Fasciitis, Defined

The plantar fascia is the thick connective tissue that runs from the base of the heel, to the bones of the forefoot. Collectively, with intrinsic foot and ankle muscles, it supports the arch of the foot and helps transfer energy from the forefoot to the rearfoot and ankle, and up the leg.

By definition, in a truly literal sense, fasciitis is an active inflammation of that tissue.

But is foot and heel pain always plantar fasciitis? In a clinical sense, one can only have fasciitis if an active inflammatory event is occurring. Since inflammation only lasts 20 days, indeed, not everyone with persistent foot pain truly has fasciitis.

Not all tissue paper is Kleenex. Not all lip balm is Chapstick. And so it goes, not all heel and arch pain is plantar fasciitis. But as Shakespeare once said, “Is foot pain by any other name, any less excruciating?”

However, to label all foot pain as plantar fasciitis possibly limits one’s ability to quickly and effectively recover from it. Below are some other, equally common causes of foot pain.

Foot Pain: Differential Diagnosis

There are a many possible sources of persistent heel pain and arch pain. Here are the most common I see, clinically:

Soft tissue sprains and strains. There are several major muscles, tendons, and ligaments that span from the heel and ankle to the toes. Besides the plantar fascia, there are several flexor tendons — of muscles originating on the lower leg — that course their way into the foot.

Any number of these tissues can become strained under the load of road and trail running. A review of the Rules of Tissue Loading explains how a plantar surface tissue can become irritated.

However, since soft tissue tends to heal quickly given proper treatment, these causes tend to heal rapidly. Those with persistent heel pain and arch pain — who see me and other medical folks after weeks, months, and even years of pain — tend to have a pain generator of different origins:

Joint Pain. There are over two dozen joints in the foot and ankle complex. With the extreme stress of ultra trail running, these joints could become stiff, irritated, or both.

Joints — articulating surfaces of two bones — require but two things to be happy:

- Full range of motion

- Symmetrical, equal loading of surfaces

Seems simple, but running hard and long on uneven surfaces can strip a joint of those two things.

Range of motion loss. Joints get the bulk of their nutrition from range of motion. The vast majority of joints in the body are synovial: two bones surrounded by a leathery capsule filled with fluid. The cartilage surfaces receive very little blood flow.

In order to receive nutrition, the joint must “lubricate” itself with the fluid of the joint, absorbing nutrients from the fluid along its surface — via regular, full range of motion.

When joints stop moving through their full range, elements of cartilage do not get this nutrition. The cartilage dries up. And it is replaced with bone. This, by definition is osteoarthritis. Preceding that, is pain.

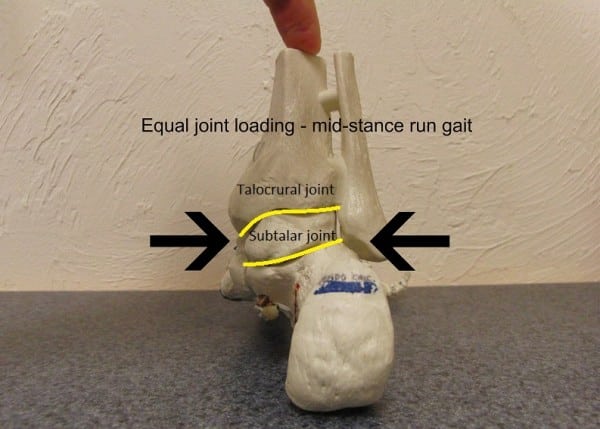

Asymmetrical loading. Joints have the ability to move — sometimes small amounts in one plane; sometimes substantial amounts in many directions. But when running, joint surfaces are designed to be loaded so that the entire surface of one bone impacts flush against the other. This promotes maximum stability; it also ensures that cartilage receives a steady dose of hydration and nutrients.

Asymmetrical loading occurs as the result of abnormal running surfaces — uneven, rocky trails, or a cambered/slanted road–or with inefficient running mechanics.

And when a joint becomes unhappy, it causes pain. Typically, a painful joint will hurt at its precise point of irritation. But joints of the ankle and foot will frequently refer pain to adjacent areas, out the sides or beneath the point of irritation, at times mimicking soft tissue pain.

How can you tell if you have a soft tissue or joint issue? Below are some comparisons:

Soft Tissue Pain Characteristics

- Succinct, reproducible, palpable tissue pain. Can you find the one spot that is tender?

- Pain with active use: when you do a toe curl or use the muscle (absent weight-bearing), does it hurt?

- Pain with passive stretch: is pain produced when you bend back your foot and toes? (again, without weight bearing)

- Pain with resisted testing: when flexing your foot and toes, is there pain?

Joint Pain Characteristics

- Dull, diffuse pain: no discernible “tender spot.” Rather, it hops around and you can’t put your finger on it.

- Pain with weight-bearing through the joint.

- Pain is worst in the morning, after prolonged weight-bearing, or after resting, then bearing weight through the joint.

- Non-weight-bearing testing — actively flexing and passively stretching the foot — is pain-free.

If your symptoms align with the joint pain characteristics — and if your foot pain fails to respond to soft tissue plantar fascial treatment approaches — you likely have joint pain.

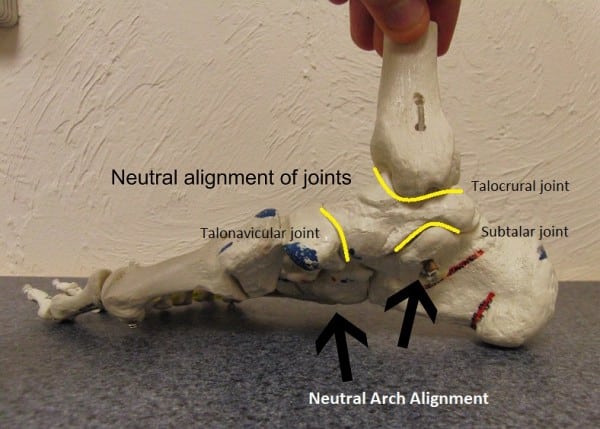

The three usual joint suspects — the talocrural, the subtalar, and the talonavicular — can all become painful and mimic plantar fascial pain. Each joint lies on the medial plantar surface of the foot, and each is prone to stiffness and asymmetrical loading during running.

Above shows a medial view of the foot, showing three main joints of the foot. The talus plays a role in all three: it is the go-between from the foot and leg bones.

From above, it forms the talocrural joint. The main motion for this joint is “up and down” — it allows the toe-up/toe-down action that occurs in the run stride.

This joint is prime to get stiff, especially with repetitive downhill running: rather than smoothly sliding and gliding, hard downhill trail running can cause jamming forces of the talus into the tibia and fibula. And when this joint gets stiff, it can refer pain in any direction around the talus — front or back of the ankle (mimicking both anterior tibialis tendonitis and Achilles tendonitis, respectively), or it can spit pain out the side — namely the medial ankle and arch.

Between the talus and the calcaneus — or heel bone — is the subtalar joint. It is designed to move in several axes, but its primary axis of motion is medial to lateral. This joint is of little consequence to the healthy, normal runner: minor motions occur depending on the gait cycle.

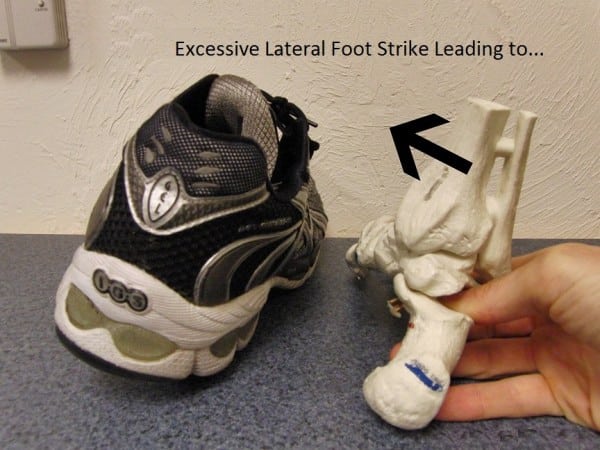

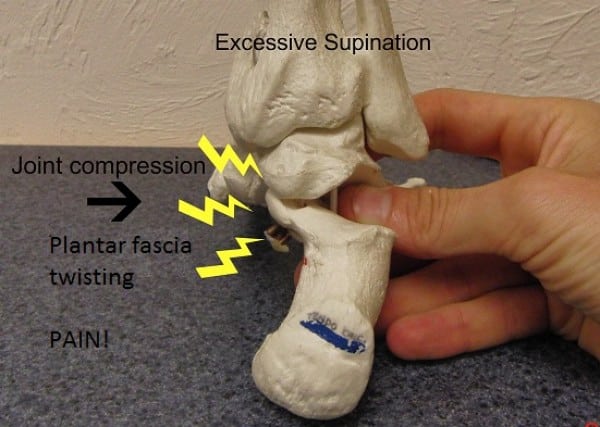

However, deviations or inefficiencies — namely in the foot strike pattern — can cause significant pain emanating from the subtalar joint. Excessive lateral foot strike can cause stressful joint compression to the medial aspect of the joint — mimicking plantar fascial pain!

Lastly is the talonavicular joint. This joint is the primary conduit from the fore and midfoot to the ankle and leg. The navicular bone is the “keystone” of the arch. Stiffness or irritation here can also cause significant arch pain.

The following are some illustrations of how mechanical forces can cause joint and soft tissue pain:

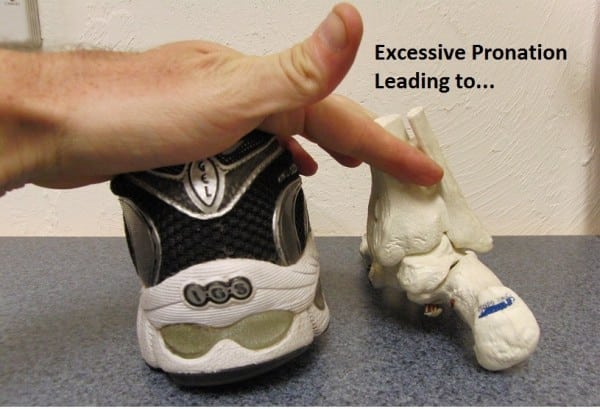

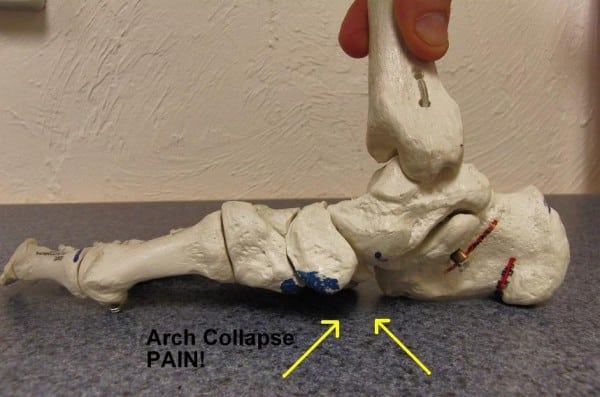

Excessive medial foot landing leads to over-stressing of the medial arch, or “arch collapse.” This stresses all tissues of the plantar surface and is the primary etiology of true plantar fascial pain.

Equally common, especially for faster trail runners, is excessive lateral foot strike:

Excessive lateral striking significantly compresses the medial joint surface of the subtalar joint. This compression accounts for a large percentage of non-plantar fascial foot pain cases. It refers pain at its site, but also farther down into the arch and along the heel bone.

Too much lateral strike can also cause plantar fascial torquing: the heel rotating to the right (in the above picture), but the forefoot rotates to the left as it contacts the ground — adding a twisting force to the fascia.

Nerve pain. Perhaps the most unrecognized and overlooked factor in heel and foot pain is nerve pain. The peripheral nerves of the ankle and foot originate in the brain, course through the spine, exit the low back and pelvis, and must course — fluidly — through the soft tissues of the entire leg.

Repetitive impact forces from running — often combined with compromised spine posture from running all day (or, in our normal lives, sitting) — can cause these nerves to develop “hitches.” This is a concept called nerve tension.

Nerve tension accumulates in the spine and legs with age, injury history, and running volume. When nerves lose mobility, they begin to create pain — often very similar to soft tissue or joint pain, including plantar foot pain.

And because the same repetitive or excessive impact forces that create joint and soft tissue pain also create nerve tension, it is very common for a runner to present with both joint/soft tissue and nerve pain overlay at the same time.

Almost every runner (and most other folks) has some degree of nerve tension. Here’s a test:

Sit with your back against a chair, head and shoulders upright. Extend your knees straight, with toes up. Note the degree of “stretch” in the back of your legs. Then, slump your head and shoulders. Any increase in stretch sensation is nerve tension from tensing the nerve at the head and neck.

Nerve Pain Characteristics

- Pain at rest — the hallmark sign of nerve pain overlay: do you have any symptoms in your foot when at rest, namely sitting (specifically, with prolonged sitting, long after you’ve stood on it)?

- Symptoms described as burning, buzzing, or dull aching.

- Other symptoms higher up the leg, specifically: lumbar, buttock, posterior thigh, calf, or shin pain.

Very often, a runner who applies soft tissue or joint treatment concepts will get partially better, but fail to fully recover because they fail to address the nerve tension component.

Runners and clinicians, alike, need to recognize the existence of nerve tension and treat it concurrent with any soft tissue or joint irritation.

Treatment Approaches

Please discuss any of the following treatment approaches with your doctor, physical therapist, or chiropractor before performing.

Soft tissue

These are straightforward because everyone who [thinks they have] PF does them:

- Rest, ice, soft tissue mobilization, stretch, strengthen.

Real, actual soft tissue plantar pain will heal rapidly, given correct doses of the treatments above. Those who do not respond to that approach likely have a joint or nerve issue.

Joint pain

The two treatment approaches to joint pain in the foot include full restoration of joint range of motion and symmetrical loading.

Range of motion restoration

Ankle dorsiflexion. Normal ankle dorsiflexion is about 20-30 degrees beyond a 90-degree bend at the ankle. If you cannot stretch this far — or if you have symptoms in front, or anywhere around the ankle joint — your symptoms might be due to stiffness there. To mobilize a stiff talocrural joint, try the following:

Perform a standard calf stretch, with a few minor adjustments: be sure your stretch foot is perfectly straight ahead. Keep the foot flat, lean forward with a straight knee until full tension.

Then, slowly bend the knee as much as possible without allowing the heel to rise. Slowly oscillate between a bent and straight knee. This mobilizes the tibia and fibula over the talus, restoring motion to this joint.

Subtalar inversion and eversion. A normal heel bone should be able to “wiggle” about 10-20 degrees side to side. To self-test, cross your ankle over the opposite knee. Grasping hold of your ankle with one hand, drive firmly downward with your opposite hand on the inside of your heel bone.

Can you move it, at all? If not, and you have heel and arch pain on the bottom/medial side of your foot, your symptoms may be coming from a stiff subtalar joint.

To self-mobilize, perform the maneuver described above with firm, slow, on-and-off downward pressure. The degree of motion will be slight, but the potential for pain relief is substantial when motion is restored here.

The author applying a straight downward pressure to the heel bone, stabilizing at the ankle. A normal heel will “wiggle” a few millimeters in both up and down directions.

Midfoot arch. A normal midfoot will have some degree of give, both to the hands and when standing on it. In standing, a normally mobile foot should “sink” a few millimeters to the floor.

Shoe orthotics are intended for those who are hypermobile in their arch: their arch joints are excessively flexible, and the arch “collapses” (typically defined as one centimeter or more) in weight bearing.

However, far more often than not, runners have hypomobile arches — they simply don’t move enough. These folks typically respond poorly to orthotics (often with no improvement, and sometimes they worsen pain).

A hypomobile, stiff arch will benefit from self-mobilization. If you have symptoms that originate farther down the foot, near the apex of the arch — and your foot lacks any give in standing — try the following mobilization:

Stand with the stiff foot down. Place your opposite heel directly on top of the stiffest area — typically the navicular bone, which lies directly in front of the tibia-fibula complex. Gently, then progressively bear down with substantial weight onto the navicular.

This may seem scary — test it first. A stiff navicular will give very little, even with full pressure. Pain usually comes from skin compression. “Stomp” on and off 10-20 times. Perform before and after running, and/or in the morning, when stiff joints tend to be stiffest.

The author, performing a mid-foot self-mobilization in standing. Try with soft-heeled shoes on, if too sore with direct skin contact.

Joint Loading Factors

Loading the joint equally is vital to joint happiness. Orthotics can be helpful for those with hypermobile feet, as they can prevent arch collapse. They are also helpful for slower runners with shorter stride lengths. A short stride tends to include excessive vertical forces (up and down motion).

This vertical loading bears down on the medial arch — beyond the capability of muscles, tendons, and the plantar fascia to support it. An orthotic can aid in sustaining the arch. But ultimately, an efficient stride that emphasizes normal hip mobility with greater forward momentum is most important in preventing arch collapse.

Other important factors for symmetrical, low-stress loading include the position and angle of foot strike. The foot should always land as close to directly beneath one’s center of mass as possible. A foot that strikes in front, tends to strike:

- On the heel;

- On the outside edge of the foot (heel or midfoot); or

- On the mid or forefoot, laterally-biased.

A heel strike creates considerable stiffness through the talocrural and subtalar joints. A lateral strike might cause asymmetrical loading of the subtalar joint, and/or a twisting, torquing force through the midfoot and plantar fascia (see photo above). A midfoot or forefoot strike — significantly ahead of the body — will stress out those joints or strain the plantar fascia.

The most simple, sustainable, and important way to correct a foot strike issue is addressing it proximally with:

- Proper forward trunk engagement, and

- Moving the hips such that the foot is “pulled” beneath the body

After ensuring proper foot placement beneath the trunk, shoot for a whole-foot strike, where all elements of the foot are absorbing and sharing impact forces.

Nerve Pain Treatment

To treat nerve tension, refer to the test above, except make one slight adjustment:

Sit in a chair, slumped forward. Slowly extend the affected leg with toes up. As the foot and lower leg rise, slowly extend your head at the same speed. The degree of stretch should be significantly less, but still present.

Hold one second, then slowly lower. This is referred to as a “nerve floss” exercise: the head gives the nerve slack that is taken by the foot, and vice versa. Repeat 10 to 20 times, and perform three to four times a day, especially before and after running. Here is a video link for the exercise.

Call for Comments (From Bryon)

- Have you suffered from heel pain, plantar fasciitis, or other foot pain?

- How did you heal your plantar fasciitis, heel pain, or other foot pain?