Russia’s brutal war against Ukraine is a colonial war (Snyder 2022) fought by Ukraine as a war of decolonisation, historical, cultural and linguistic. Tensions and conflicts surrounding language, especially around the status and asymmetric roles of Ukraine’s two main languages—Ukrainian and Russian—form part of its post-colonial legacy. Overt and covert policies which promoted the Russian language and culture during imperial and Soviet times not only persecuted Ukrainian, but also brought about a separate ‘language’: a mixed Ukrainian-Russian speech commonly known as surzhyk. Surzhyk is a form of colloquial speech rather than a written language and is spoken in urban and rural settings. The features of surzhyk, drawing on both Ukrainian and Russian, can include mixing at the level of sentence, vocabulary and pronunciation. The term “surzhyk”was originally used to refer to a mix of wheat and rye flour, a lower grade, impure flour. The term was later extended to denote the mixture of Ukrainian and Russian languages, and is a similar concept to “trasianka”, Belarusian-Russian mixing in Belarus (Kittel, Lindner, Tesch and Hentschel 2010). In the late Soviet-period dictionary of Ukrainian, it is defined as “elements of two or more languages, joined artificially, without adhering to the norms of the literary language; impure language” (Hrynchyshyn and Humetska 1978).

The phenomena of surzhyk

The emergence of Ukrainian-Russian mixed speech is the result of the prolonged coexistence of the two languages, coupled with the language policies of the Russian empire and, subsequently, the Soviet Union, which created favourable conditions for its development and growth (Kent 2011). Some sources trace the origins of surzhyk as far back as the seventeenth century (see Kent 2011). However, many scholars see the industrialisation and urbanisation of Ukraine in the nineteenth century as the turning point (Bilaniuk 2005). When Ukrainian-speaking peasants moved to cities for work they encountered Russian-speaking administrators and bureaucrats. These urbanized peasants, lacking formal education, attempted to incorporate as many Russian elements as possible into their speech, owing to the prestige associated with the Russian language. However, their communication was primarily restricted to individuals from similar backgrounds, leading to the emergence of surzhyk.

Surzhyk is not unique. Intensive contact between two or more languages, can lead to the development of mixed languages and hybrid speech forms (Meakens and Stewart 2022). However, the precise nature of Ukraine’s surzhyk remains a topic of continuing discussion among scholars (Hentschel 2023). Some view surzhyk as a single language variety, others — as a ‘chaotic’ blend of Russian and Ukrainian speech. Linguistic anthropologist Laada Bilaniuk emphasises that the Ukrainian-Russian surzhyk is an umbrella term encompassing a range of language phenomena (Bilaniuk 2005). She also distinguishes “native” forms of surzhyk, used by Ukrainians who speak it as their native (first) language, from “transitional” surzhyk, spoken by those who mix languages due to incomplete knowledge of the language they are attempting to speak, being it Ukrainian or Russian (Bilaniuk 2005).

In the background of Ukraine’s historical milieu, the complexity of the surzhyk phenomena can be attributed to multiple source codes (languages or dialects), including spoken Ukrainian, spoken Russian, Ukrainian regional dialects, and literary Russian and Ukrainian languages.

The politics of language

The perception of surzhyk has been at all times underpinned by particular views of Ukrainian and Russian. In professional literature, these views are referred to as language ideologies defined as sets of beliefs, feelings, and conceptualisations about language structure and use, which are socially shared and shaped by cultural settings (Piller 2015).

The long-lasting effects of Russification, a linguistic colonisation which was most aggressive in eastern and southern Ukraine, have led to internalised ideologies about Ukrainian, Russian, and, the “language in-between,” surzhyk (Seals 2019). Soviet cultural and linguistic conservatism, rooted in the well-established traditions of imperial Russia, promoted linguistic purism by elevating a “pure” (Russian) language and portraying it as the only legitimate tongue (Bilaniuk 2005), The languages of the other Soviet republics were seen as by far less prestigious and less legitimate while non-standard varieties, such as dialects and surzhyk, were stigmatised. In contrast to Russian, perceived as the language of interethnic communication, modernity, progress and industrialised cities and towns, Ukrainian was associated with backwardness and rural settings. Ukrainian was intentionally portrayed as a “dialect” of Russian, not even a separate language, which reinforced it association with impurity and mixed Ukrainian-Russian speech and its opposition to “pure” Russian.

The rise of independent Ukraine witnessed similar purist trends with the need to legitimize Ukrainian as the (only) language of the Ukrainian nation. This led to an ideology that aimed to distinguish Standard Ukrainian, the “high-status language” of the urban population, from the Ukrainian language varieties used in rural settings. Originally developed in Russified cities, surzhyk was now perceived to be spoken in villages, while Standard Ukrainian was promoted as the language of the urban elite. In the 1990s, surzhyk became iconic of cultural lowness and was seen as “contamination” caused by Russification (Bilaniuk 2017). The independence period is also associated with the so called “neo-surzhyk” – a Russian-based variety different from the “old” Ukrainian-based surzhyk developed in Ukraine since the late 19th century (Hentschel 2024). Neo-surzhyk arose as an outcome of a reverse process – Ukrainianization – whereby people who grew up speaking Russian later transitioned to speaking Ukrainian in everyday life.

Since the late 1980s and Ukraine’s independence in 1991, there has been a noticeable shift from Russian to Ukrainian, a trend that intensified following the 2004 Orange Revolution and gained significant movement during the 2013-2014 Euromaidan protests, also known as the “Revolution of Dignity.” The pivotal moment came in 2014, when Russia’s military aggression in the east of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 led many Ukrainians reasses their relationship with the Russian language, viewing it as the language of the ‘enemy’ and a symbol of Russia’s occupation. The all-out invasion of February 2022 further increased the number of people who embarked on the process of “linguistic conversion” (Bilaniuk 2020) – a deliberate shift from using Russian to speaking Ukrainian – referred to as perekhid in Ukraine. Neo-surzhyk thus appears a transitional step in linguistic conversion, an in-between stage in the process of crossing over to Ukrainian from Russian (Kudriavtseva 2024).

“Surzhyk is a transitional stage”: shifting language attitudes during the war

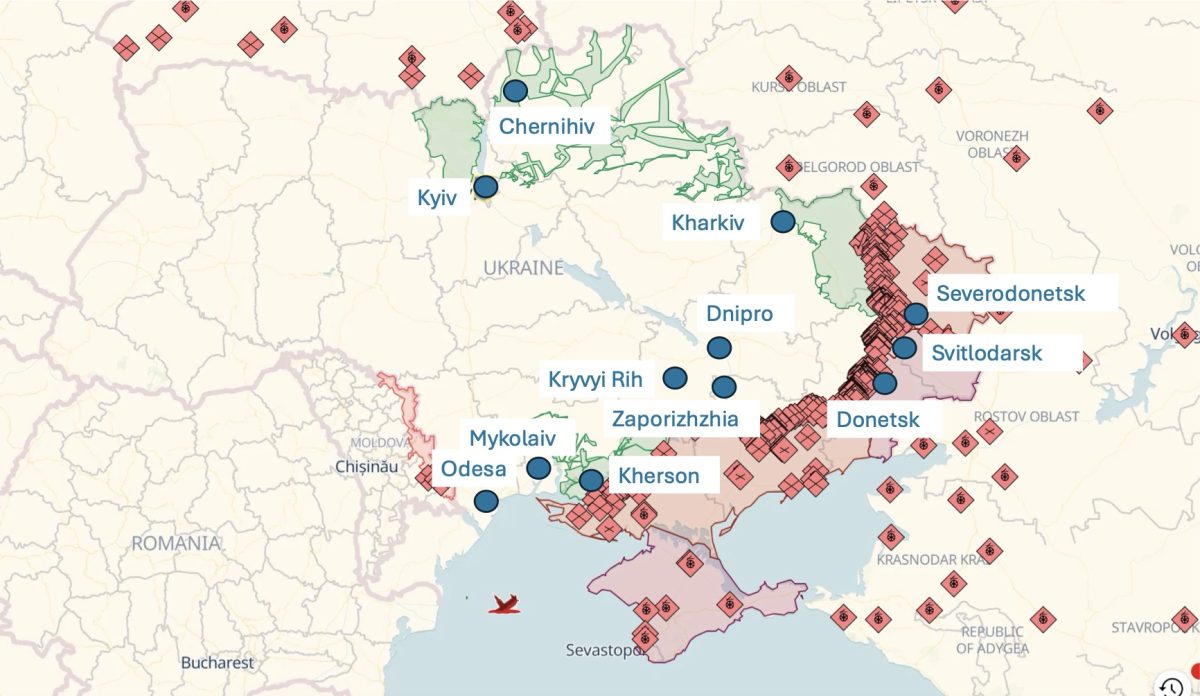

Ethnographic research on Ukraine’s linguistic converts (Kudriavtseva 2023) shows a re-evaluation, a revision of the views of surzhyk in the context of Russia’s war of aggression. The linguistic converts interviewed for this research are urban, well-educated and middle-class adults aged between thirty and seventy who come from industrial cities and towns in eastern and southern parts of Ukraine (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Dnipro, Odesa, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Kryvyi Rih, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Chernihiv, Severodonetsk and Svitlodarsk), as shown in Figure 2. These participants have been enrolled in Ukrainian language education initiatives (language courses and clubs) organised by activists and volunteers with the aim of supporting the people undergoing linguistic conversion.

As predicted by the nature of ideological views, the participants tend to show complex and often conflicting beliefs about non-standard varieties. Though the interviews were held in fluent Ukrainian, almost all the participants stated that their goal was to master Ukrainian well. This testifies to their perception of their current proficiency in Ukrainian as still in need of perfection, the view imposed by the idea of purism whereby there is an “ideal” standard which is hard to attain. Some of them see surzhyk as a part of Ukraine, and consequently of the Ukrainian language. Others perceive it as an “alien” element, an “impure” language, expressing the view which goes back to the colonial times. Though less prominent, the latter attitude shows up in the dislike of surzhyk as a patois, a low-status vernacular, spoken in rural settings. Surzhyk is found to be “inappropriate”, “incorrect”, “putting the teeth on edge” and “not the Ukrainian language”. Sometimes it is also linked to poor education.

Some of the participants draw strong parallels with their education in Russian, either during the late Soviet era or in the 1990s: “We were very closely monitored in terms of our Russian pronunciation. Even when we were not taught Russian as a subject, phonetic mistakes pulled our grades down” – says 47-year-old Natalia from Kherson who developed her critical attitude towards language mixing during her university years. 57-year-old Olha (Kherson) perceives surzhyk as something “disgusting”. Olha is now still confident that whatever is said in surzhyk “would be better expressed in Russian [if not in Ukrainian] because “language purity must be maintained”.

However, the majority of linguistic converts express more positive views about surzhyk. The two most frequent attitudes are the view of it as a transitional stage and the overall perception of surzhyk as being better than Russian. “You can’t avoid it. Surzhyk is a transitional stage. And every person will go through it… This is normal. Surzhyk is better than Russian. In my own view. It takes time. Then a person will feel uncomfortable [speaking in surzhyk] and will anyway start speaking correctly. It takes time” – says 34-year-old Oksana from Mykolaiv. Though still framed within the ideology of linguistic purism, this view of surzhyk signals a shift from the traditional purist attitude which opposed surzhyk and the standard. The “transitional” view posits surzhyk as a “first step for those who want to switch to Ukrainian” (Tamara, 49, Odesa) and thus attributes it to the Ukrainian language.

The idea of surzhyk as an integral part of Ukraine’s linguistic landscape surfaces in the recognition of it as one’s “native” language, a distinct dialect spoken in different areas of Ukraine and an everyday colloquial language, a “folk” language, spoken not only in villages, but also in industrial cities. This positive appreciation is captured in the expression “a colour of language” mentioned by 46-year-old Iryna from Kharkiv. Surzhyk sounds natural, authentic, “not artificial” and “not purified” – remarks 59-year-old Vladyslav from Kryvyi Rih who perceives surzhyk as an urban koiné.

The associations of proximity, relaxation and intimacy accompany these positive perceptions of surzhyk and attribute it to the Ukrainian language seen as going beyond the standard itself. This appropriation of surzhyk testifies to the elevation of non-standard varieties, including mixed forms, in relation to “pure” language, and primarily Russian. Rather than opposing surzhyk and Standard Ukrainian, the majority of linguistic converts now see the Ukrainian-Russian mixed speech as an opposite to the language of the former empire, which is perceived by them as an “alien” language, something imposed on Ukraine during the colonial times. Their transition from Russian is an expression of solidarity against the current Russian aggression, as well as a previous centuries-long Russian colonization, a sign of national unity and a validation of Ukraine in all its diversity via the use of different varieties of the Ukrainian language. For linguistic converts, the judgment of surzhyk to be better than Russian is a form of protest against Russia-imposed stigmas and stereotypes and a powerful anti-colonial statement.

Surzhyk as a protest

During the late Soviet years, non-standard language was used as a form of protest against Soviet regime (Bilaniuk 2017) by violating the supremacy of “pure” Russian. Surzhyk has embodied a protest against colonial views ever since. By rejecting the idea of “pure” language, surzhyk has been employed as an expression of freedom: from the Russia-imposed linguistic ideals and Russian political dominance, from Russia-backed Ukrainian politicians, from the Russian claims of “non-existent Ukraine”.

One of the first and still most well-known Ukrainian artists who purposefully chose surzhyk as a means of artistic expression was the comic artist and singer Andrii Danylko, who performed as a train attendant Verka Serduchka. In the early 1990s, his popularity as a stand-up comedian grew so he started singing in surzhyk and won the second place in Eurovision in 2007. Like the speakers of surzhyk, among other things, Andrii Danylko received a lot of criticism from linguistic purists. However, from the larger perspective, his Eurovision performance can be decoded as a symptom of the hybridity of Ukrainian cultural space and an anti-colonial statement (Pavlyshyn 2019).

In the Euromaidan revolution of 2013–2014, boiovyi (fighting) surzhyk arose as a symbol of Ukraine’s solidarity (Bilaniuk 2016). It was used as a protest against the Russia-backed political order and a re-appreciation of Ukraine’s own cultural and linguistic diversity. A cultural project popularizing non-standard language varieties re-brands surzhyk as Slobozhanskyi dialect. The Kharkiv-based music band “Kurgan & Agregat” launched in 2014 promotes the non-standard forms of Ukrainian beyond the everyday life of rural and provincial spaces. Through local ways of speaking, the musicians embrace their local identity positing surzhyk as something to be proud of. Here, music and language become a means of solidarity, erasing established cultural and social hieararchies.

Using surzhyk as a literary instrument, contemporary Ukrainian writers have promoted its richness and authenticity through their own works and public engagement. In 2023, the second year of the all-out war, a group of young Ukrainian linguists published a magazine, “smt surzhyk”. Aiming to preserve surzhyk’s diverse forms, its authors consider surzhyk “a linguistic and cultural island of freedom, which was abandoned for a long time” (Petrov 2023).

The ongoing war and the process of de-Russification of Ukrainian culture and public space have enabled to contest the earlier perceptions of surzhyk as a derogatory and ‘impure’ language. Depending on speakers and audiences, surzhyk has now become a means for negotiating identities, as well as a vehicle of protest and solidarity. Before the Russian invasion, the use of Ukrainian, surzhyk, or Russian was considered a private matter, in the new reality, making a choice of which language to speak has become a matter of conscious decision either in personal communication or artistic expression. While someone who has been previously comfortable being in between these languages purposefully decides to choose a particular identity, others consider surzhyk as an instrument of cultural and political protest. On social, cultural, and daily levels, surzhyk has developed its meanings from being a “local variation” of Ukrainian to a language of local community and solidarity.

This appropriation of surzhyk testifies to the growing tendency towards elevation of Ukraine’s linguistic varieties and acceptance of variation, which goes against the colonial idealisation of standard and strictly traced norms. This allows to critically re-examine the legacy of the colonial past and is an important step in Ukraine’s linguistic and cultural decolonisation.

Figure 1

English translation: “And what are you doing, Yolop, hah?

Don’t you see, I am holding the house…because it is swaying…like a drunk”

Source: Public domain via Wikimedia commons.

Figure 2

Participants’ places of permanent residency prior to 2022 full-scale invasion. Shades of red and pink represent the territory occupied by Russia; green indicates the territories liberated by the Ukrainian Armed Forces in 2022. Generated by OpenStreetMap – Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license (CC BY-SA 2.0), accessed 13 March 2024.

References

Bilaniuk, Laada. 2005. Contested Tongues: Language Politics and Cultural Correction in Ukraine. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bilaniuk, Laada. 2016. “Ideologies of Language in Wartime.” In Revolution and War in Contemporary Ukraine: The Challenge of Change, edited by Olga Bertelsen, 139–60. Stuttgart: ibidem Verlag.

Bilaniuk, Laada. 2017. “Purism and Pluralism: Language use Trends in Popular Culture in Ukraine since Independence.” In The battle for Ukrainian: A comparative perspective, edited by Michael Flier and Andrea Graziosi, 343–363. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bilaniuk, Laada. 2020. “Linguistic conversions: Nation-building on the self.” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Societies, 6, no. 1: 59-82.

Hentschel, Gerd. 2024. “Ukrainian and Russian in the lexicon of Ukrainian Suržyk: reduced variation and stabilisation in central Ukraine and on the Black Sea coast.” Russ Linguist 48, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-023-09286-9

Hrynchyshyn, Dmytro Hryhoriiovych and Humets’ka, Lukiia Lukianivna. 1978. Korotkyi tlumachnyi slovnyk ukrains’koi movy. Radians’ka shkola: Kyiv.

Kent, Kateryna. 2011. “Language Contact: Morphosyntactic Analysis of Surzhyk Spoken in Central Ukraine.”

Kittel, Bernhard, Lindner, Diana, Tesch, Sviatlana and Hentschel, Gerd. 2010. “Mixed language Usage in Belarus: the Sociostructural Background of Language Choice”, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, vol. 2010, no. 206, pp. 47 71. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2010.048

Kudriavtseva, Natalia. 2023. “Motivations for Embracing the Ukrainian Language in Wartime Ukraine.” Ukrainian Analytical Digest, 1, 12-15. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000623475

Kudriavtseva, Natalia. 2024. “Ukraine’s Wartime Classrooms: L1 Russian Speakers’ Transition to Ukrainian.” Accepted in the special issue of Sociolinguistic Studies “Language and War: Sociolinguistic Shifts in the Ukrainian Language Situation in the World,” edited by Volodymyr Kulyk and Laada Bilaniuk.

Meakins, Felicity, and Jesse Stewart. 2022. “Mixed Languages.” The Cambridge Handbook of Langauge Contact, 310–43, Cambridge University Press.

Pavlyshyn, Marko. 2019. “Ruslana, Serduchka, Jamala: National Self-Imaging in Ukraine’s Eurovision Entries.” Eurovisions: Identity and the International Politics of the Eurovision Song Contest since 195, edited by Kalman, J., Wellings, B., Jacotine, K. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9427-0_7

Petrov, Valerii, 2023. ‘Movnyi ostrov svobody — rozmova z sozdatielnitsamy zinu «smt surzhyk»’, Spilne, 4 July 2023, https://commons.com.ua/uk/rozmova-z-sozdatelnicami-zinu-smt-surzhik/.

Piller, Ingrid. 2015. “Language Ideologies.” In The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction, edited by K. Tracy, T. Sandel and C. Ilie. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi140

Seals, Corinne A. 2019. Choosing a Mother Tongue: The Politics of Language and Identity in Ukraine. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781788925006/html

Snyder, Timothy. 2022. “The war in Ukraine is a colonial war.” The New Yorker. Published 28 April 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/essay/the-war-in-ukraine-is-a-colonial-war

Further Reading on E-International Relations