For years I thought that breaking a collarbone was a cycling rite of passage. Something emphasised every season on Eurosport when a crash occurs and Carlton Kirby yells “Oh, my life!” for the umpteenth time and Sean Kelly responds with his signature, doleful “Yesss, well…” before a wincing rider touches his shoulder gingerly, prompting a qualifying: “Looks like a collarbone…”. While other injuries are available, as Kirby might suggest, they just don’t quite seem as, er, cyclingy.

Adam having finished the DeeJay100 Gran Fondo with a broken collarbone

(Image credit: Adam Jones)

I first broke mine in 2019, during the DeeJay100 Gran Fondo near Milan, hitting the apex of a slippery roundabout at over 56kmh. I remember shakily getting to my feet and thinking ‘I’ve broken my collarbone.’ What informed this opinion was the extreme pain and the fact that my shoulder now felt like a packet of dropped biscuits. When I returned home to the UK, my physio told me that nothing was broken. I soldiered on. Until in 2023, when I took another tumble – and a GP confirmed my new break was, well, not as bad as the original.

I was ordered off the bike for six to nine weeks. I waited a fortnight before attempting a turbo session. As if this wasn’t machismo enough, when I posted my 30-minute tootle on Strava, a club mate responded: “Two weeks? Surprised you lasted that long. I was back on the bike within 48 hours.” And so, it began. I was now bombarded with well-intentioned suggestions to “get a plate”. It was almost like a refrain in a Sondheim musical.

I began to wonder why, as an amateur time triallist of a certain vintage, my coach and friends were urging me to get a plate? Where had this need to hasten my recovery come from? Were they merely aping what happens amongst the pro ranks? Or, is there more to it?

What happens in the pro ranks?

During his pro career Alex Dowsett broke his collarbone four times, each one on the right side of his body. Curiously though, none were during actual competition. In 2015, a bad prang during training resulted in a broken clavicle. “I could feel the bone pressing against the skin,” he told me. “I knew I’d broken it.”

Alex Dowsett, photographed by Cycling Weekly

(Image credit: Future)

The injury required plating but this was anything but a ‘simple fix’: “The plate had popped through the skin. I could both feel it and touch it. My surgeon said ‘We need to get that out now’. The surgery took just 25 minutes, followed by a day’s recovery,” he says matter-of-factly. Adding that, with the plate now removed, “I had holes in the bone, so it needed to recalcify.” Nevertheless, as he prepared for his Hour Record Attempt, Dowsett was back on a static bike a week later and out on the roads of Essex not long after.

“If it is plated, it’s closer to being fixed,” Dowsett told me, reinforcing the prevalent narrative.

The medical theory is that a plate confers mechanical stability and helps the injury to begin the healing process, without the need to wait several weeks for the callus to form a junction between the broken bones. Without plating, the reparative stage for a broken clavicle starts within a week of the initial injury, but won’t be sufficiently strong enough to sustain normal use for six to eight weeks.

In 2011, Dowsett signed as a neo-pro with Team Sky joining at a time when orthopaedic surgeon and talented amateur road and track rider Dr Jason Roberts was bringing his specialist training and experience to the British squad for a second season. “I was a trauma surgeon then, so my skills definitely fitted with the day-to-day needs of a World Tour team and its riders,” he explains. “I spent about thirty days a year on the road with Sky, during which time I dealt with loads of collarbones. Not least because at their level, Sky were operating about three teams at any one time and, of course, the team was fully aware that a collarbone injury is devastating when it happens.”

Roberts knows injuries are the last thing a team wants: “The DS (Directeur Sportif) just wants to know when the rider will be ready to race again. But riders take a big risk if they’ve recently had surgery and return too quickly, as they can still break the bone around the site of the plate and, of course, there’s an inherent risk with metalwork and its removal. In my experience, both amateur and professional cyclists will go looking for someone who can fix them quickly, so they can get back to doing what they love.”

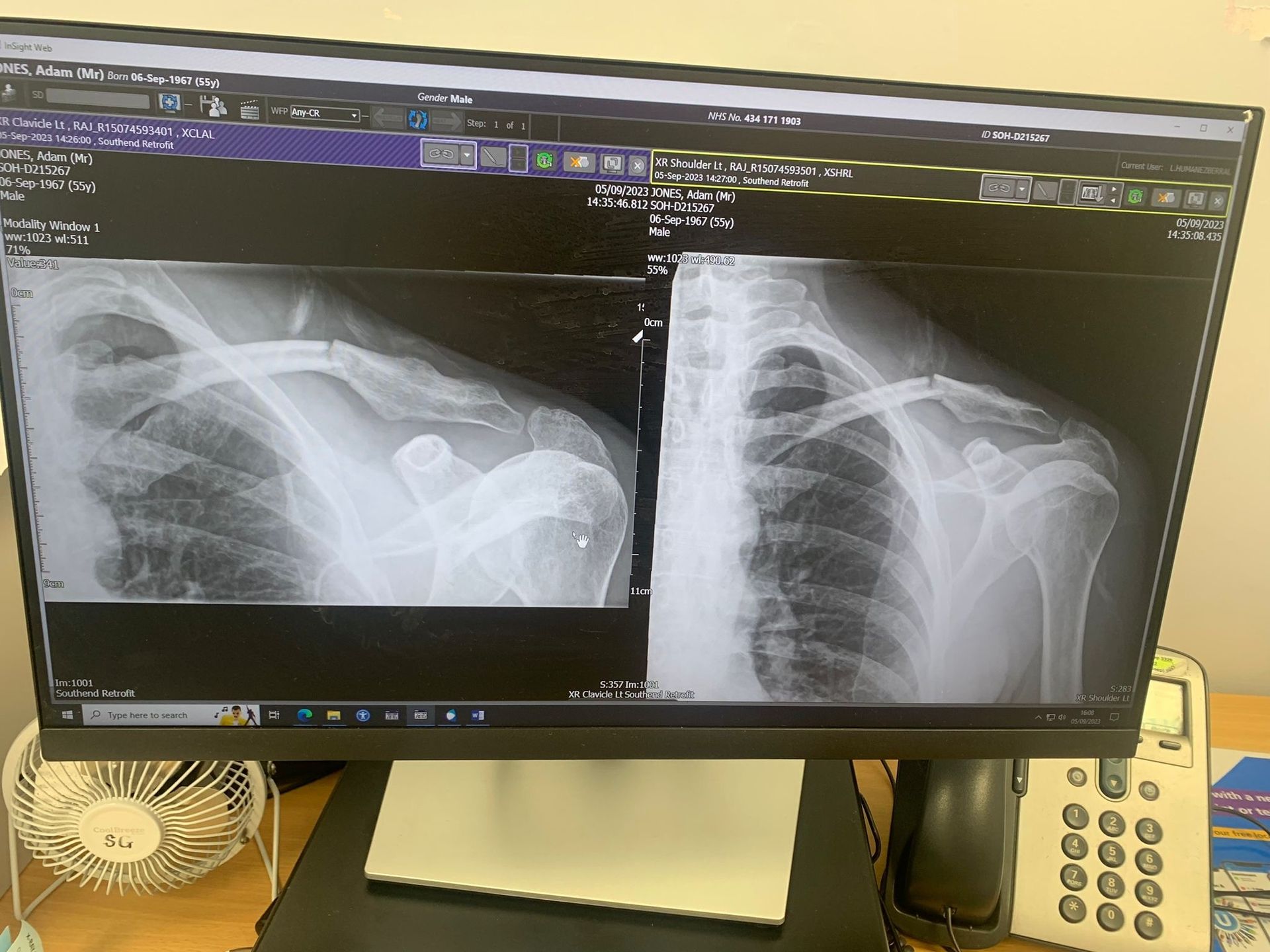

(Image credit: Adam Jones)

Looking at my x-rays, Roberts said: “You were lucky. You hadn’t displaced majorly but the previous injury, which broke the Outer Third, that’s the one that affects the ligaments that attach to your shoulder blade. It’s not a good area for healing.”

When I press him on whether a plate would have helped me, as I was so frequently advised, he says: “Part of my training was spent in the French Alps, so I saw a lot of skiers and snowboarders with collarbone injuries because they’re largely caused when you put your hand down in the process of falling. Everybody, without question, we just plated them. That was the culture. Here in the UK though, we hardly ever do this, unless the patient is a professional sports person. The reason for this is that, in the vast majority of cases, most people can be left to heal.”

A need to ‘bounce back’

So why do people who make a living from, or do sport as committed amateurs demand surgery?

“They want to train and compete. It’s who they are. If you fix them (with a plate), they will get back to their normal function quicker. However, the healing process for the injury is still the same.”

Offering advice for making a successful recovery, Roberts suggests making full use of the initial downtime, something not advocated by my cycling pals.

“As soon as you can functionally use the limb you should but before then it is worth bearing in mind that other factors are at play. In terms of skin abrasion, the inflammatory process is immense. So, time relaxing is really beneficial. You won’t hugely de-train in those first two weeks after an accident, so if you can have time off (work and the bike) take full advantage. During the ‘acute’ phase, which is around the first week to ten days, you are very susceptible to issues relating to the inflammation around the injury, so rest is very much best. Apply your common sense, which I know is often lost in sport but if you try to go back too early, you run the risk of fracturing again and putting yourself back to square one. So be cautious.”

This last point rang particularly true for me. During one of my initial, tentative 30-minute sessions on Zwift, I went for a sprint effort and the gearing suddenly slipped. I was thrown forwards and the pain was off the scale. I was screaming. As I tried to compose myself, my shoulder felt like it had rebroken and I did indeed feel like I’d taken a retrogressive step. After that, I was far more careful and less willing to get my ego out in Watopia.

Roberts understands what had compelled me into that painful moment: “Sports people are impatient and invested in their passion, but when something is taken away from you – such as your ability to train or compete – you have to refocus and reset your goals. For example, when I was at Sky, Wiggo (Sir Bradley Wiggins) broke his collarbone during the 2011 Tour (de France) and then refocused for La Vuelta.”

Of course, once the surgeons have either done their thing or not, whatever the individual case may be, the next phase is making sure you have good quality rehab. Being given a set of exercises to do every day gave me an important psychological boost, I felt that I was doing something and indeed, with each passing week, I could attempt and achieve more in the gym.

Eventually, I felt physically able to get on my bike and head out onto local roads but needed a good friend to accompany me, ‘just in case’. The next hurdle was riding solo and retracing the route where I crashed. Having ticked those boxes, I began to recover both my physical and mental strength.

Reflecting on the whole experience, I was reminded of a comment Wout van Aert made a few years back: “Falling down is an accident. Staying down is a choice.”

Dr Jason Roberts’ top tips for recovery

Make use of the downtime, is the advice

(Image credit: Jason Roberts)

Orthopaedic surgeon and rider Dr Jason Roberts has worked with World Tour teams, assessing injuries and advising on rehabilitation protocol. He is now Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon and Clinical Director of the Department of Orthopaedics at the Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Clydebank, Glasgow.

Roberts shares his tips for a healthy return…

- Unless you’re a pro in the middle of a stage race, make full use of that initial downtime, as the old adage goes ‘rest is best’. Time relaxing is really beneficial. You won’t hugely de-train in those first two weeks after an accident, so if you can have time off (work and the bike) take full advantage.

- Follow the advice given by the professional looking after you. Only they know the true nuance of your individual injury, not your pal in the pub!

- Alex Dowsett has said: “Movement is a good thing; pain is a bad thing. Do as much as you can until it hurts. Then don’t do it anymore!” He’s right, movement is the most important thing. We have a saying in orthopaedics that ‘movement is life’, so try to make sure you’re keeping the joints above and below the injury active as best as you can

- Prepare to readjust your goals and timelines. Doing this early will help you stay positive and realistic.

- Apply your common sense, which I know is often lost in sport but if you try to go back too early, you run the risk of fracturing again and putting yourself back to square one. So be cautious.

Five pro collarbone breaks

Bradley Wiggins after crashing during stage seven of the 2011 Tour de France

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Bradley Wiggins: The roof fell in on Sky’s chances of a much-vaunted Tour de France podium when the reigning British champion went down in a pile-up 40kms from the finish line on Stage seven of the 2011 race. At the time, Wiggins was lying 6 th in the General Classification. He used the downtime to prepare for a tilt at La Vuelta later that summer and was rewarded with second place, behind teammate Chris Froome. In 2012, Wiggins achieved his dream of winning the Tour and a week later, claimed the gold medal in the men’s time trial event during the London Olympics.

Alex Dowsett: Essex can be a painful place in which to train, as the then Movistar rider Dowsett found to his cost. His hopes of breaking the UCI World Hour Record were dealt a blow when he suffered a crash on home roads back in January 2015. Five months later (2 May 2015) He did indeed set a new world record of 52.937 kilometres (32.894 miles), beating Rohan Dennis’ previous record by almost half a kilometre. A fortnight after that, Dowsett claimed his first overall stage race victory, winning the Bayern Rundfahrt.

Mark Cavendish crashes out of the 2023 Tour de France

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Mark Cavendish: The Manx Missile came to grief in the 2023 edition of the Tour de France, as the 38-year-old attempted to finally beat Eddy Merckx’s record of 34 stage wins. Crashing out on the 8th stage, Cavendish later posted a selfie on his Instagram account showcasing a lurid post-surgery scar. Having postponed his retirement, the Astana Qazaqstan rider has already tasted victory in the early part of the year, winning Stage four of the Tour of Colombia and has his sights firmly set on making history in France this summer.

Sean Kelly: In 1987 the Irishman abandoned the Tour in tears after what had seemed an innocuous-looking crash during Stage 12. He had initially tried to ride on, but was eventually forced to loosen the straps on his toe clips and climb off the bike. A favourite for the podium, his frustration was captured by the race TV cameras. A year later he finally added a Grand Tour to his palmares, winning Spain’s La Vuelta.

Tyler Hamilton: If Kelly was hard, then Hamilton was double-hard. Literally. The American won a stage of the 2003 Tour despite a double-fracture of his right clavicle and reportedly ground his teeth in agony so strongly that 11 needed replacing. Prior to his victory, Hamilton had been riding with his collarbone taped into place but what made his stage win in the Pyrenees all the more remarkable was that not only his margin over his closest pursuers was almost two minutes, was that he basically rode an 80-kilometer time trial into Bayonne. Notably, Lance Armstrong trailed in behind Hamilton in 24th place, with Jan Ullrich and Alexandre Vinokourov also unable to match the CSC team leader’s heroics.