The collapse of the Soviet Union precipitated the dismantling of the old bipolar world order and triggered debates about the merits of unipolar versus multipolar security environments. It became evident that the traditional Cold-War framework, centred around the strategic competition between two superpowers, no longer fully captured the complexities of contemporary power. However, traces of the Cold War context are still a lingering presence on the Korean Peninsula. Historically, Korea has been a strategic hotspot for great powers, with its division resulting from the East-West confrontation. The Korean War, which witnessed significant casualties from both American and Chinese forces, ended in 1953 with a ceasefire agreement but without a peace treaty. Throughout much of the Cold War, peace and stability in the Korean Peninsula were maintained through the tight military alliances of the two Koreas with rival great powers, relying on a credible mutual deterrence based on relative power parity (Lee 2004, 263). The logic of the balance of power remained a dominant factor in any security calculations regarding the Korean peninsula.

During the Cold War, North Korea held a distinct image and relative power compared to its present portrayal as a failed, isolated, rogue state. During its heyday, coinciding with the height of the Cold War, North Korea surpassed its southern counterpart economically, militarily, and politically. While South Korea was still an underdeveloped agrarian region, North Korea stood as the second most industrialised and urbanised society in East Asia after World War II. Pyongyang received substantial economic subsidies and military support from the communist bloc, and its ground forces were estimated to be one-fourth of the population by 1958. Under Kim Il-sung’s rule, Pyongyang fought against the US-led UN force during the Korean War, with extensive aid from China and the Soviet Union. Despite massive bombing, North Korea experienced rapid post-war economic recovery up to 1960s and was considered as a model by many countries. It actively supported anti-imperialist “liberation movements” in the Third World (Cha 2012, 19-62; Taylor 2015; Vu 2019). The country also had a significant diplomatic presence, becoming the only socialist country to join the Non-Aligned Movement in 1975 while having previously signed Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance treaties with China and the Soviet Union in 1961. In both material and ideological senses, North Korea was more advanced to its southern counterpart (An 1983; Scalapino and Lee 1972; Suh 1988).

In his 2021 speech at the Supreme People’s Assembly, Kim Jong-un identified ‘the increasing complexity and multidimensionality caused by the transition toward the new cold war structure’ as a major feature of the changing international situation (KCNA 2021a). Subsequently, Kim has promoted his concept of the “new era of the Juche revolution” as a solution to adapting to the “new challenging situation” (KCNA 2021b, 2021c, 2022). The revisiting Cold War discourse in North Korean rhetoric and the introduction of the ‘new era of Juche’ represent new developments. This paper aims to uncover the cognitive frameworks that shape North Korean leaders’ decision-making processes by examining the distinctive perceptions of the Cold War era and the Juche ideology regarding the country’s security environment, and how these perceptions may influence North Korea’s security choices in the new Cold War era.

Ideas play a crucial role in North Korean strategic choices. The official strategic culture, Juche, has unquestionably played a major role in rationalizing Kim Il-sung’s decision-making in domestic and international policy spheres. A sizable literature documents studies of North Korea’s formal ideology – Juche (often translated as ‘self-reliance’ or Kimilsungism). Some views Juche to be a creative Marxist-Leninist construct that helps North Korea to achieve revolutionary goals (Cummings 1974, 34-36; An 1983; Rodong Sinmun 1977, 1); a North Korean version of Maoism (Yim 1983); a tool to justify Kim Il-sung’s domestic political struggle (Scalapino and Lee 1972); a modulator of external balance between two great powers during Soviet-China disputes (Suh 1988; Kim 1977; Kim 1973); and a justifier of links between the DPRK and the developing world (Suh 1988). Juche is an intriguing belief system that encompasses all aspects of North Korean socio-political life. The DPRK leaders’ strategic thinking is likely to have crystalised during the Cold-War experience. The idea of Juche kept evolving under Kim Il-sung’s regime, absorbing features of nationalism, socialism, and Confucian hierarchical collectivism. It eventually become a comprehensive ethno-centric philosophy and a Weltanschauung by the early-1990s.

Juche-determined policymaking requires discussions on its intrinsic meanings – revealing cognitive framework of the leaders’ perceptions on security environment and strategic preferences. An examination of the Cold War period’s North Korean strategic culture provides valuable insights into the formulation of its policies and foreign relations from its own premises. The socialised strategic culture of North Korea was shaped by its unique historical experiences. Changes in exogenous conditions interacted with the socially constructed central paradigm of strategic culture and strategic preferences, leading to variations in its ‘rational choice’ through a domestic strategic cultural prism.

This article first discusses the strategic central paradigm and preferences pertinent to North Korea’s Juche ideology, which were shaped during the Cold War experience. It then explores the continuation of Juche in “new Cold War” strategies under Kim Jong-un’s leadership, concluding with the implications of these findings. This article takes a novel approach by adopting Alastair Iain Johnston’s strategic culture analytical framework to examine the dynamics of North Korea’s domestic and foreign policies under the banner of “national security” during the Cold War. It reveals that the regime has historically perceived its security environment a realpolitik central paradigm, and its strategic behaviour has been a parallel of offensive and charm offensive in joining different global and regional movements which serve its own course of political goals.

Strategic culture and strategic behaviour

During the 1980s, the debate between rationalism and constructivism highlighted the centrality of security. In an objective sense, security is synonymous with power. Security is gained through accumulation of power. Material factors have traditionally been the main manifestation of national security. States’ strategic choices are determined by the pre-given international anarchical structure and motivated or restricted by the distribution of power (Waltz 1979, 131). Thus, state actor’s interests and identities are identical and exogenously derived (Waltz 1979, 289). However, a subjective understanding of security emphasises the absence of fear of threats to the national interests. Subjective security is gained through relations among states, as the social nature of states allows for the development of ideals of security (Farrell 2002, 51). These ideals and ideas shape states’ actions in preserving and protecting national interests. In addition to material factors, culture and ideational factors contribute to the complex decision-making process and play a crucial role in shaping states’ strategic choices (Katzenstein 1996; Wendt 1995).

Strategic culture studies during Cold War period often focused on ideology. The US-Soviet rivalry highlighted the national cultural and ‘stylistic differences’ between the two ideological groups (Gray 1981, 22). However, strategic culture does not refer solely to historical roots; it also suggests that ‘once [a] distinctive approach to strategy takes hold, it tends to persist despite changes in the circumstances that gave rise to it’ (Snyder 1990, 3-4). Giving the realist structure dominance during the Cold War, strategic culture is used by scholars to explain behaviour in the last resort.

It is based on the idea that strategic preferences are influenced by historical and cultural factors, limiting strategic choices and shaping a state’s present strategic behaviour (Johnston 1995, 3). Every society has their own ideational system which legitimates their social activities. Ideational factors are fluid rather than static, human agents interpret actual events through frames of their knowledge while new events modify their ideational ‘facts’ and therefore produce new knowledge. Cognitive beliefs about ‘reality’ are continuously being learned and tested by social actors. Culture exhaustively shaped agents’ reality apropos “the national styles and traditions” and “hopes and fears” and “with individuals affected by a distinctive cultural heredity” within the cultural context (Booth 1979, 135-136). Colin Gray (1981, 22) defines strategic culture as “modes of thought and action with respect to force, derived from perception of the national historical experience, aspiration for self-characterization… and from all of the many distinctively experiences of geography, political philosophy, of civic culture, and way of life.” Agents will only make encultured decisions and these decisions directly descend from culture. Strategic culture is an invaluable starting point for understanding a group’s salient “social reality”, including its perceptions of national interests, identity, and shared norms (Booth 1979, 142; Macmillan, Booth and Troop 1999, 9; Johnston 1995a, 1996).

The strongly centralized, monolithic, and rigidly oppressive political system may suggest that policymaking is a personal decision rather than one reflecting collective interest. However, as Solingen (2007, 125) suggested, even in a regime like North Korea, decision-makers “must craft supportive clientelistic networks” for regime maintenance. This article looks for the continuity of the strategic culture across its leaders in Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un’s reigns. Monarchs and domestic agents will through the continuation of symbolic interaction between domestic preferences and exogenous changes, select the best strategic option based on their causal beliefs. Strategic culture plays a role in shaping their conscious strategic choices, serving as both impetus and restraint.

Strategic culture consists of two layers: the central paradigm of a strategic culture and strategic preference (Johnston 1995a, 1995b, 1996). The central paradigm represents a state’s assumptions about the nature of its security environment. This includes the perception of [1] the nature of human affairs in international environments refers the ideas of whether conflicts are aberrant or inevitable in human affairs (Johnston 1996); [2] the nature of the networks with other actors refers to how the strategists view different relationships including alliance and adversary and the support it offers and the threat it poses; and [3] the resources to address conflicts and the efficacy of the use of these resources refers how the strategists view “the ability to control outcomes and eliminate threats and the conditions under which it is useful to employ [means]” (Johnston 1996). The second layer of strategic culture is a set of ranked strategic choices. It reflects, at an operational level, how the strategic culture suggests to decision makers the most efficacious modus operandi for dealing with threats or security problems. It is possible that strategic options might overlap across different societies; however, the weighting of each strategic choice is distinct in each society.

The object of analysis consists of books Pyongyang officially published about Juche, archives from Woodrow Wilson Centre, and secondary resources that directly mentioned the quotes and speech from North Korean leaders. Symbols derived from selected text reflect “social reality” that has been constructed historically in a society in terms of its security environment. These symbols include strategic axioms, metaphors and analogies in the selected texts, such as frequently used idioms, phrases which can serve as valid descriptions of the strategic context or keywords that supply action-oriented justifications to adversaries.

The strategic-culture approach aims to explain a set of symbols, beliefs or attitudes that is derived from history. In the first layer of strategic culture, symbolic analysis will be applied in investigating three components from the Juche idea that reflect Kim Il-sung’s Central Paradigm of a strategic culture during Cold War (1948-1990). In terms of the second layer of strategic culture, the selected text combining empirical decision-makings made by North Korean leaders can serve as valid descriptions of DPRK perceived strategic context and supply action-oriented justifications. Drawing on Johnston’s symbolic analytical approach, the original thesis utilized a notation system consisting of three numerals for reference. For example, (23.237.2) indicates that the symbols mentioned can be found in resource number 23, on page 237, and within the second line. This method was chosen to represent a broader range of symbolic analysis across various documents; however, for the purpose of article publication, only selected representative references were included. A complete list of symbolic analysis annotations can be provided upon request.

The central paradigm of Juche

The nature of international security environment

As encapsulated in the principle of Juche, the world is viewed as being in constant revolutionary struggle between exploiters and the oppressed, this being an inevitable historical stage of social progress (Kim 1975f, 562; Kim 1978, 145; Kim 1978c, 237; Kim 1982a, 2). Being geopolitically important to great powers, Korea became a victim. Frequent references were made in speeches and writings to Korea’s humiliating subjugation by foreign powers (Kim 1976a, 189; Kim 1975a, 191; Kim 1975b, 202; Kim 1970, 4; Kim 1982a, 29; Ri 2012, 2). They note that revolutionary struggle needs to be informed through study of Korean realities – the history of Korea in particular (Kim 1978c, 233-237; Kim 1978d, 252; Kim 1978f, 394). Korea is historically a venue for great power competition – Qing China, Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Japan, the Expansionists including Britain, France, Germany and Italy, Czarist Russia and Meiji Japan (Ri 2012, 2; Kim 1976b, 466; Kim 1970, 2-12; Kim 1978a, 145). Following the liberation of the country from Japan in 1945, the immediate national partition was another product of the competition of foreign aggressors (Kim 1976a, 204). The country fell apart (Kim 1978c, 235-237; Kim 1976a, 9; Kim 1976b, 130). While the northern part was seen as progressively achieving its national independence, southern Korea had ‘fallen into the road of colonial slavery and reaction’ and were subjugated to ‘US imperialist occupation’ (Kim 1976b, 131; Kim 1965a, 24; Kim 1975b, 202; Kim 1970, 4; Kim 1978d, 249).

During the early-Cold War, the struggle was between opposing forces: imperialist and anti-imperialist; revolutionary and counter revolutionary. Imperialist and capitalist forces sought to install an exploitative system and their aggressive self-interest precipitated disorder and endangered world peace (Kim 1975b, 202; Kim 1978c, 237). Confronting imperialist and capitalist forces is a worldwide trend (Kim 1975f, 547; Kim 1982a, 24-29). Working-class uprisings against oppression and exploitation are effective at aggravating capitalism’s inner contradictions (Kim 1976a, 189; Kim 1976a, 3; Kim 1978b, 198; Kim 1978e, 356-357; Kim 1982a, 8-9; 23-25). In late-1980s, Juche evolved into a revolutionary spirit against all domination including by colonial, imperial and capitalist forces that sought to occupy others’ territories or barter away the sovereignty of nations.

Conflicts and struggles are inevitable but also desirable (Kim 1975e, 539; Kim 1978a, 145; Kim 1982a, 3). Juche reflects Kim’s idea of Korean exceptionalism. Koreans shall be revolutionary, to fight actively against any type of domination by others (Kim 1975e, 540; Kim 1982a, 2-3). In 1960s-1970s, rather than accept East-West détente and rapprochement between the PRC and the US, Kim Il-sung continued to apply his Juche ideology on the course of revolutionary struggle. The exceptional character of North Korea in the world affairs defined by Juche, Lankov (2013, 67) suggests ‘self-significance’ to be closer to the original meaning – “the need to give primacy to one’s own national interests and peculiarities”. In North Korean leaders’ words, the two characters of Self-significance are identified as revolution for national unification free from foreign forces and construction of a superior socialist society (Kim 1976a, 189; Kim 1970, 5; Kim 1978b, 191).

Relations in power politics

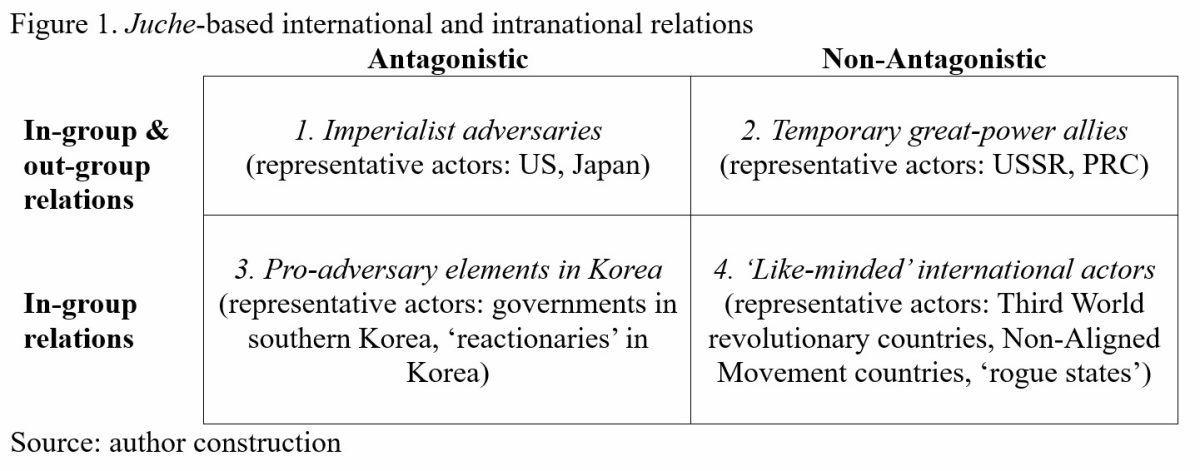

In Juche worldview, conflicts could be antagonistic or non-antagonistic, and between in-groups and out-groups or within in-groups. The (potential) adversaries or (potential) allies include state and non-state actors. The perceived natural relationship with these actors can be categorized in a two-by-two matrix (Figure 1).

(1) Imperialist adversaries

The first cell contains foreign imperialists who have principle antagonistic and uncompromising conflicts with Pyongyang. Korea is a victim of territorial partition and national division by imperialists (Kim 1976a, 192; Kim 1975a, 191-193; Kim 1970, 3; Kim 1978d, 240; Kim 1975b, 204; Kim 1976b, 136; Kim 1971, 13). During the Cold War, the US is seen as the main imperialist forces of aggression and war and the most vicious enemy (Kim 1976a, 192; Kim 1975a, 193; Kim 1970, 3; Kim 1975c, 315; Kim 1978d, 240). In Kim Il-sung’s writing, American disruptive influence since the Korean War consistently hindered Korean people from achieving a unified and independent nation; the US seduced landlords, comprador capitalists and traitors, to enforce a colonial feudal system in Korea’s southern half (Kim 1975a, 193; Kim 1971, 13; Kim 1978d, 240&248; Kim 1991b, 18). The nature of imperialism is aggressive (Kim 1978d, 241; Kim 1965a, 26). Conflicts with these actors in cell 1 (Figure 1) are zero-sum transactions. One could eliminate these adversaries through military, economic and ideological superiority – both material and ideological conquer (Kim 1975b, 251; Kim 1975f, 548; Kim 1976d, 410; Kim 1982a, 23&25). This zero-sum struggle is depicted as a ‘protracted war’ (Kim 1978c, 235-236).

(2) Temporary great-power allies

The second cell (Figure 1) contains anti-imperialist forces – ‘foreigners’ such as the oppressed workers, peasants and nation-states that support and follow revolutionary lines (Kim 1976a, 9; Kim 1976b, 130; Kim 1976d, 420&424). The Cold War alliance with Soviet Union was not Kim Il-sung’s choice; rather, it was given during anti-Japanese war and later anti-American camp (Hershberg 1995). The security environment and imperialists’ aggressive nature, and the momentary interests of North Korea nurtured collaboration with the international partners supporting both ‘national liberation of the southern half’ and ‘revolutionary struggle’ (North Korean Constitution Article 16; Kim 1976a, 195; Kim 1970, 49). The movement enlisting anti-imperialist international actors was given the Soviet label of ‘proletarian internationalism’. Stalin and Kim had very different interpretations of the term. The Comintern extended the Soviet Union’s capabilities and made it the ‘supervisor’ of other fraternal communist parties and international revolutionary movements (Kim 1975a, 193; Kim 1971, 13). But Juche did not accept an external international centre for proletarian movements (Kim 1976a, 201; Kim 1970, 333).

For Kim Il-sung’s the international proletarian alliance and Juche were compatible under a framework that incorporates internationalism under self-reliant nationalism (Kim 1976a, 196.). This was also observed in the narrative on accepting foreign aid and military support (Kim 1976a, 195&201; Kim 1975f, 548). Pyongyang managed to reconcile its Juche policies and relations with Cold War partners. The principle of ‘a complete equality and mutual respect’ between the fraternal parties and non-interference in each others’ domestic affairs was also listed in the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance between North Korea and the Soviet Union (July 6, 1961) and with China (July 11, 1961). From the mid-1960s, as the China-US-Soviet Union triangular power structure became clear, North Korea has adopted the same approach to manage its relations with China (Kim 1975e, 542; Kim 1975f, 567). With actors in cell 2 (Figure 1), despite recognizing that conflicts with these actors may arise due to great powers’ self-interested actions that may be harmful for the principal of ‘self-reliance’ (Kim 1976a, 196; Kim 1975a, 200; Kim 1975e, 542; Kim 1975f, 567). In general, the conflict is not antagonistic, the association with these actors depends on the global context and Korea’s national interests; namely, forming a united international front against principal adversaries in cell 1 (Figure 1).

(3) Inter-Korean dimensions

The third cell contains capitalist or imperialist elements in both northern and southern Korea including the imperialist installed ‘puppet government, bourgeois reactionary, landlords and comprador capitalists’ (Kim 1976a, 141; Kim 1975a, 199; Kim 1975b, 202; Kim 1975c, 315; Kim 1976a, 6; Kim 1978a, 148-149; Kim 1978d, 257; Kim 1978f, 394). In inter-Korean relations, intra-party competition began in the-1940s. Following the Japanese surrender, the two Koreas developed their individual systems with both regimes asserting sovereignty over the entire peninsula. Mutual antagonism led to the Korean War, but unification failed because of external imperialist forces. Kim’s prism suggests that actors allying with imperialists are the primary reason to drive Korean people into a fratricidal north-south conflict (Kim 1976a, 9; Kim 1976b, 130; Kim 1976d, 420&424). These actors are self-interested traitors, assisting the imperialist US in pursuing a policy of splitting the nation and bartering away national duty (Kim 1976a, 141; Kim 1975a, 191; Kim 1976b, 133; Kim 1978d, 249; Kim 1978f, 394; Kim 1958, 195). As in cell 1, actors in cell 3 engage in zero-sum conflict (Figure 1).

The two Koreas not only compete for material gains, a zero-sum symbolic competition for international prestige also persists in the Korean Peninsula (Kim 1965b, 4-6; 12; Kim 1995, 117-123). Unification by military means was considered by Kim Il-sung when the South was governed by Rhee Syng-man (1948-1960) and Park Chung-hee (1962-1979). Up-to 1970s, Pyongyang possessed superior military capability as well as political and economic stability. Seoul’s military regime was unpopular at home and not favoured by the US. Park shifted from militarism to monetarist strategy in the 1970s. The regime normalized its relationship with Japan and pursued an export-led economic development. Roh Tae-woo (1988-1993)’s ‘northern politics’, aimed at normalizing relations with communist regimes including USSR and China, only added to Pyongyang’s perception of a ‘hostile’ environment. The fear also comes from North Korea’s own Juche strategy of reunification. Kim Il-sung planned to unify the country through constructing a superior Juche society and mobilizing the people in the South against an inefficient regime (Kim 1978f, 394). During the Cold War, Pyongyang endorsed zero-sum inter-Korean relations. Allying with imperialist forces, the South Korean governments in cell 3 (Figure 1) were undoubtedly adversaries. The existence of an increasingly more advanced South became a real threat to Pyongyang because of the latter’s zero-sum (absorption by the South) legitimate competition in the international arena.

(4) The ‘like-minded’ international actors

The fourth cell (Figure 1) contains non-antagonistic other-than-great-power actors in international movements that opposed imperialism. Imperialists not only militarily infiltrated ‘national liberation’ movements in Asia, Latin America and Middle East, but also introduced imperialist rules through international regimes and institutions (Kim 1971; Kim 1978c). Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1968 is one example. Five countries (China, France, US, USSR and UK) were acknowledged as nuclear-weapon states; free will was denied to others to nuclearize. Noticing its former wartime allies among the nuclear suppressors North Korea began to share technological knowhow with non-aligned near-nuclear or potential nuclear countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Libya and Pakistan. DPRK jointed the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) as a full member in 1975, after the movement had matured enough to have influence on global affairs. The negotiation between nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear-weapon states was seen by Pyongyang as an unequal exchange serving one side’s interests. Although North Korea signed the treaty under foreign pressure, its view on NPT as an imperialist tool to strengthen great powers’ domination remained unchanged (Kim 1978c).

DPRK actively promoted diplomatic ties with NAM for two reasons. First, Kim wanted to engage with great powers diplomatically without losing his political independence (Kim 1978c, 233-237; Kim 1995, 123-135). Despite Third World elites commonly viewing the NPT as another instrument of superpowers in centralizing power in world politics, they do not want an uncontrolled nuclear proliferation. Rather than advocate bomb-making, most Third World elites view a nuclear-hedging strategy as a diplomatic resource. Namely, a grand bargain for receiving nuclear technology for civilian use from nuclear-weapon states (nuclear suppliers) and non-nuclear-weapon Third World states (potential nuclear proliferator), was favoured. It is important for both domestic and international audiences to understand that North Korea was not being forced to embrace international norms by US/RoK’s ‘engagement’ policies, rather, it engaged in a bilateral political dialogue vis-à-vis the US. This intention was evident in US-DPRK dialogue during President Jimmy Carter’s visit in 1994. Secondly, grouping with NAM symbolizes the North Korean regime’s superiority –autonomy from Soviet Union and China, particularly when compared to the South Korea-US alliance. Kim’s calculation of a strategic wedge between the Soviet Union and China was based on his desire to be free from foreign interference in domestic affairs. NAM viewed the confrontation as evolving into one between forces of domination and opponents of domination (Krishnan 1981). The declaration of fortifying the unity of anti-imperialist independent forces was to achieve independence in world affairs outside strategic East-West competition. With the actors (from the Global South) in cell 4 (Figure 1), the relations are emotional and sympathetic binding.

Resources to address conflicts

(1) Correct leadership

This might be the most disruptive element that applies to all conflict resolution. But under Juche, the correct leader is a premise for success (Kim 1976a, 72&64; Kim 1975a, 198; Kim 1975b, 251; Kim 1975f, 548; Kim 1976a, 9; Kim 1965b, 73). Kim Il-sung’s regime was a party-state system under Suryong’s (or Supreme Leader) guidance. Article 11 of the Constitution states that “the DPRK shall conduct all activities under the leadership of the Workers Party of Korea (WPK)”. The ruling party and its leader are integrated. Suryong plays the central role in the Party is the latter being an autonomous nucleus promoting and advising the Suryong. Suryong is the brain of nation and the only legitimate decision maker, playing the role of ideological unifier and revolutionary guide of the people. The Party guides the government, and the army (KPA) is the revolutionary military arm of the Party. Hence, KPA was under direct control of WPK. The revised Constitution in 1998 under Kim Jong-il’s rule abolished CPC (the highest standing leadership body) and the presidency, divided government and Worker’s Party of Korea, while strengthened NDC and the cabinet. The party-army relationship has changed but the one-man ruling mechanism remains. Three institutions (government, army and party) were divided and equally supervised by Suryong.

(2) The use of force

Three righteous purposes were found to legitimately use force in Juche: [1] North Korean border defence; [2] reunification and freeing the people in South Korea when a world-wide war is unleashed; [3] instituting a revolutionary line in South Korea by de-stabilising the system in the south.

Juche identified two resources used by imperialists to force Korean people to submit to foreign power – ‘martial rule’ and ‘cultural rule’ (Kim 1992; Kim 1982a, 29-30; 1982c). ‘Martial rule’ was instituted through military coercion – occupation of Korea by advanced military forces. Juche as a worldview indicates that imperialist powers are always prepared to conquer smaller nations bereft of self-reliant military capability (Kim 1970, 3; Kim 1982a, 34). The humiliating historical subjugation of Korea is a result of its military unpreparedness. Kim has repeatedly criticised the Yi Dynasty and nationalist movements during Japanese colonisation for not building up a strong military or relying on external forces to achieve independence (Kim 1965a, 2; Kim 1975a, 191). Lacking self-reliant defence, “Koreans still relied upon the expanse of their country’s geography and its vast man-power base to fight a successful protracted war and to deter an aggressor from instigating an invasion of their soil” (Kim 1992, 64; Kim 1982a, 45). ‘Cultural rule’ refers to working with domestic reactionaries and traitors to eliminate the national independence of Korea. Kim criticized outdated traditional Korean political thought – sadae jui (serving the great powers or flunkeyism) (Kim 1975a, 193; Kim 1970, 49; Kim 1992, 143). He makes it explicit that it will never be the case that great powers would help small nations to gain independence. To blindly follow foreign countries and believe that relying on external forces could bring durable prosperity and peace to Korea, is to be devoid of the spirit of self-reliance. It is essential for Korean people to solve their national problem by themselves. Regarding Koreans, ‘if people do not fight themselves, people will lose faith’. Regarding external powers, “foreigners are not in a position to solve the internal affairs of our nation” (Kim 1992, 17). Both ‘imperialist rules’ have suggested the paramount importance for Pyongyang to develop an indigenous advanced conventional defence system against superpowers (Kim 1978a, 171).

Using force during a world war is justified under the spirit of Juche. In such a war, North Korea will liberate South Korea. This option dominated the early-Cold War bipolar confrontation. Due to the unavoidable contradictions between the two world camps, war was inevitable as long as different classes and imperialist powers existed. Before the world-wide revolutionary war, DPRK should concentrate on military preparation and strengthen the situation for the world revolutionary task. The unified international anti-imperialist force will defeat imperialists and achieve reunification of Korea. In addition, guerrilla warfare tactics were used to destabilise domestic politics in South Korea (Kim 1976a, 57; Kim 1976c, 276; Kim 1978d, 248). Subsequent military infiltrations (Kim 1976a, 137; 195) and mobilization of patriotic and revolutionary forces (Kim 1976a, 72-73) in the southern half is part of unification strategy. For instance, three attempts were made to assassinate ROK presidents in 1968, 1982 and 1983, and bombs was detonated in South Korea’s international airport in 1986, and on ROK Air Flight 858 in 1987.

(3) Political education

There were various ‘problematic’ actors that lack national consciousness, according to Kim. They included traditional ones such as factionalists, domestic opportunists, conservative nationalists, as well as new ones such as the youth who had not experienced the ‘Liberation War’ (Kim 1976a, 141; Kim 1975a, 191; Kim 1970, 4; Kim 1991b, 173). They were either the direct pro-foreigner factions (pro-Chinese, pro-Japanese, pro-American and pro-Russia) that seized power in domestic affairs or were indirectly influenced by pro-foreigner factions (Kim 1992; Kim 2008; Kim 1975b, 202-223). Since the 1970s, Kim Il-sung noticed that youth who had not really suffered in the Fatherland Liberation War during Japanese colonisation and the Korean War had begun to ‘disdain the significance of Korean revolution’. To solve these problems, elimination of direct foreign influence was sought on one hand, and correcting their faulty ideas through patriotic education was sought on the other hand (Kim 1978e, 344-350). Kim called for transforming the ‘lost people’ or ‘self-interested’ people, by ‘political work’, to become useful for a united front to reject dogmatism and formalism (Kim 1982a, 58). There was increasing awareness of the limitation of a self-reliant economy in comparison with economic miracles achieved in neighbouring countries including China, South Korea and Japan. Kim appealed to all Korean people to embrace what he called a ‘righteous aspiration’ (ji-won 志遠) – satisfaction was not limited to material wellbeing (Kim 1992, 17; Kim 1976a, 139). To justify devoting all national resources including economic interests, to equipping North Korea with military capacities was the solution. To raise high levels of political consciousness makes them realise their revolutionary mission and the nature of foreign and imperialist aggressors. The fallacy of sacrificing material well-being in pursuit of long-term happiness, through gaining freedom from colonial slavery, was unquestionably the leader’s intended human rights abuse. The political-moral-based rather than economic rationale-driven policies had also been used in Chollima (or ‘Flying Horse’) movements during the 1950s. Kim Jong-il relabelled the same approach ‘March to Hardship’ during the Arduous March in mid-1990s and caused a mass humanitarian crisis.

North Korea strategic preference in new international security context

Security is ‘an intermediate rather than an ultimate goal, in which case it can be judged as a means to these more ultimate ends’ (Wolfers 1952, 492). The continuation of its central paradigm and a pattern of strategic preferences could be observed in fulfilling its political goals. Kim Jong-un’s Byungjin (or Parallel Development of Military and Economy) line emphasized two sovereign rights – survival and development. Heir to his father and grandfather, his Juche-based strategic preferences will continuously target four political goals: [1] security guarantee; [2] unification of Korea; [3] economic prosperity; [4] national independence as a sovereign state.

Active defence strategy

Woodrow Wilson Centre’s archives show convincingly that DPRK had devoted substantial national resources to build-up its indigenous nuclear programme since the late-1950s. The post-1990s distribution of power in regional and global power politics did not favour North Korea. The ‘new-Cold War’ structure may be seen as a strategic window for bandwagoning with China. North Korea and China announced their plan to renew the Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty in 2021 (Yonhap News Agency 2021). However, from Juche perspective, the strategic association with China would not give an acceptable security guarantee to North Korean defence for two reasons. First, a nuclear umbrella offered by a great power ally is not on North Korea’s strategic menu. Second, China’s security interests in the region and fears of the collapse of its neighbour’s regime and the consequence of regional security instability is its main driver for supporting North Korea (Wang and McGregor 2019). Great powers would abandon North Korea when there is a need (Kim 1976), the events were observed as a “betrayal” to North Korean include the USSR-China collaborative political interference in the mid-1950 (Lankov 2005), US-China rapprochement in the 1970s, and normalization relations of China and Japan in 1972 and with South Korea in 1992. The risk is high when counting on a temporary ally for one’s survival. In January 2022, North Korea successfully test its first hypersonic glide vehicle in the Sea of Japan. Kim Jong-un elaborated on his defence position: the country will ‘further strengthen the already gained war deterrent in terms of both quality and quantity’ (KCNA 2021d). This announcement came out with the first five-year plan to develop defence science and weapon systems.

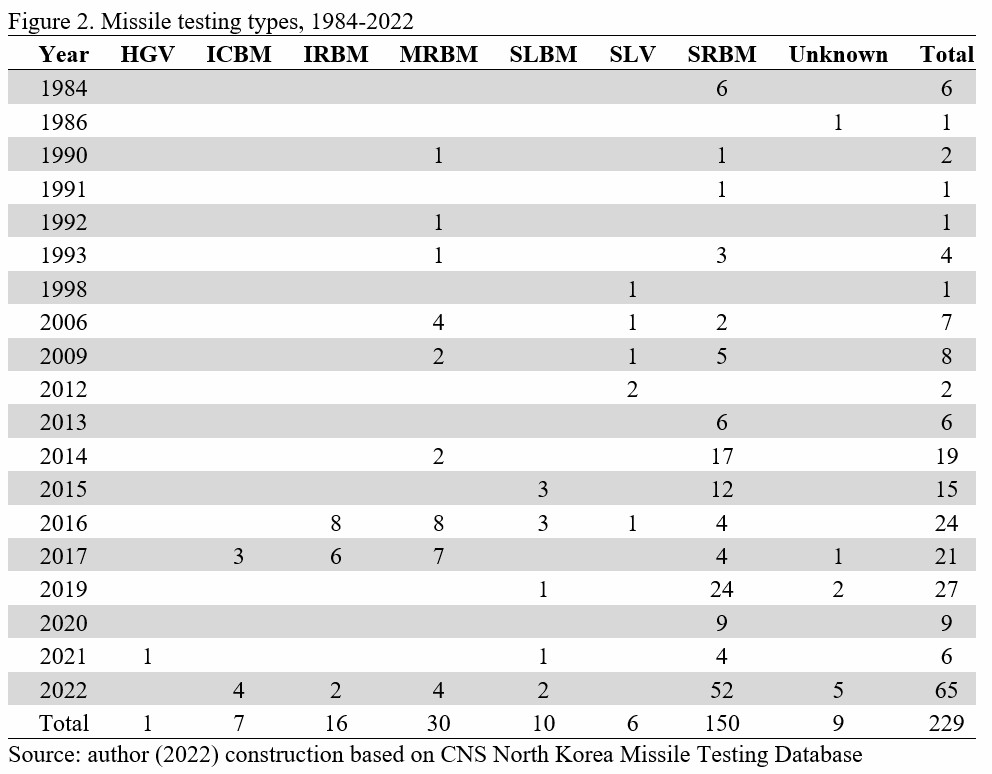

Exogenous events do impact on the DPRK leaders’ decision-making, but such interactions are taken within the Juche realpolitik central paradigm. The perceived imperialist actors’ defensive gesture often results in a more provocative response from Pyongyang, causing logical inconsistencies in its defensive deterrence argument (Cha 2002, 228-229). In 2012 DPRK proclaimed itself as a de facto nuclear-weapon state in its Constitution but promised the no-first-use principal (KCNA 2013). Despite nuclear deterrence having been developed, and land-and-sea-based ballistic missiles and anti-ship cruise missiles having been tested since 2014, training and modernizing of conventional military forces continues (Office of the Secretary of Defense 2015). DPRK has maintained the same level of military expenditure from 2000 to 2016; however, the DPRK air force and navy have greatly modernized and expanded (International Institute for Strategic Study 2016). Kim Jong-un further amended the nuclear law in 2022, declared its nuclear status “irreversible”, to underscore the no-first use principal by stating that the leader in North Korea “possess all decisive powers concerning nuclear weapons” (KCNA 2022). A more flexible nuclear strategy is adopted including pre-emptive attack. The number of North Korea’s missile launches reached a historical high point in the same year (Figure 2). Continued development of tactical ballistic missiles has led to numbers surpassing what DPRK needs for declared defensive goal. This discrepancy will continue – contributing to rising regional tensions. The wide ranges of different mobile missiles and warhead technology are indicators of Pyongyang’s determination to acquire full-fledged nuclear capabilities to ensure that any technological breakthroughs by superpowers will not compromise Pyongyang’s assured retaliation capacity. It is not an act of aggression but of capability-assurance apropos its adversaries.

Non-proliferation of nuclear weapons and stability in the region are common concerns of the US and China. Under the binary competition structure, Pyongyang’s domestic propaganda in relation to China centres on socialism, anti-imperialism, and non-interference principals in foreign relations. Seeking international legitimacy has been on North Korean leader’s agenda since it was placed on the list of ‘rogue state’. Its reckless pursuit of nuclear weapons is the major reason for the country’s human rights abuse. Pyongyang has denied all these criticisms and defended the way it treats its people arguing it is a domestic affair. Pyongyang sees itself not only as a victim of hegemonic military aggression but also of narrative aggression. China’s counter-narrative campaign, when it works, allies with DPRK’s defensive interests in a global discourse context.

Diplomatic offensive strategy on ‘independent unification’

The use of force was considered in North Korean reunification strategy during the 1950s-1980s. Kim Il-sung’s writings reveal his view that unification of Korea could either be achieved through a World War between socialist and capitalist camps or through peaceful measures. However, in today’s ‘new-Cold War’ context, as indicated in China’s 2019 Defence White Paper and US 2022 Nuclear Posture Review and National Security Strategy, both countries suggested that the new era of strategic competition centres on “integrated deterrence”. The concept, as Kathleen McInnis (2022), director at CSIS International Security Program explained: a strategy, unlike nuclear deterrent, centres on the need to “communicate intent” by all means in one’s toolbox. Two great powers are keen on a managed strategic competition rather than a catastrophic conflict or a mutually assured destruction that is heavily reliant on nuclear weapons. In the search for peaceful unification, Pyongyang’s nuclear programme primarily plays a symbolic role in portraying the North as superior to the South. North Korea’s security approach (self-reliance) instilled a sense of superiority in the Kim Il-sung regime in its legitimate competition compared with South Korea’s security approach (other-reliance). Nuclear arsenals and missile programmes become the sole material resource for DPRK realistically to keep South Korea inferior. As in the letter Kim wrote to Trump, “Now and in the future …we have a strong military without the need of special means, and the truth is that South Korean military is no match against my military” (Woodward 2020).

North Korea’s first official peaceful reunification policy – Ten-Point Platform – was proclaimed in 1993 (Kim 1993). Apart from family reunion, the reunification between two Koreas centres on commercial (tourism), aid (humanitarian and development assistance), as well as opening the channels for non-commercial exports to North Korea (Haggard and Noland 2008). However, Pyongyang’s perception of Seoul did not change from zero-sum (domination) to win-win (co-prosperity). Pyongyang is highly suspicious about Seoul’s intentions on so-called ‘win-win’ and ‘engagement’ policies. Kim Il-sung believed that to increase interaction between North and South Korea could awake the pan-Korean national consciousness and mobilize the people in the south to purge the inferior government. The same hypothesis of reunification makes today’s inter-Korea cultural and people exchange rather threatening to the North.

Inter-Korean relations is symbolically important, but it is not Pyongyang’s priority. Leaders in North Korea understands no problems can be resolved without improving the relations with the US. In terms of unification with South Korea, North Korea requires a “unified, independent, peaceful and neutral” peninsula (Kim 1982b; Kim 1991b). The preconditions under this unification framework are first to end the war in Korean Peninsula; and second the withdrawal of ‘hostile’ policies from South Korea and the US. These two principals are not mutually exclusive, and the subject to negotiate on these matters is the US. Pyongyang’s defiance of Seoul’s regime is observed both in security and economic issues. It refused South Korea to participate in denuclearisation negotiations arguing Seoul was not among the three signatories of the armistice treaty in 1953 and Seoul is not qualified to negotiate its own security due to submission its sovereign rights by harbouring US troops and military assets on its territory. In multilateral economic arrangement setting, it also rejected Seoul’s leadership of the international consortium in Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO). The dialogue with Seoul is a tactic to show the good will to the great powers for achieving the strategic objective of ‘forcing the withdrawal of US and troops from the South’ (Kihl n.d., 233). While constructing ‘superior’ image to both domestic and international audience remained significant in unification arrangements with South Korea.

Economic strategy

Byungjin line implies the simultaneous attainment of system security and development – the two are increasingly controversial under the new five-year plan of ‘military modernization’. As nuclear defensive capacity is uncompromising, such dilemma of material-ideological dual interests will persist in North Korea. The country will continuously face economic isolation. Domestic COVID-19 policies have resulted in serious economic hardship, food and energy shortage, and impoverished living standards. The political education and ideological-driven incentives only work when people’s basic needs are met. Pyongyang has historically used denuclearisation talks to gain economic rewards (Sigal 1997), but its entrenched economy has problems that cannot be resolved without international cooperation. Kim Il-sung’s instinct of internationalism under nationalism allowed international economic cooperation with socialist countries, non-aligned countries, and neutral western countries under terms of mutual respect and equal sovereign rights for all states. Comparing to nuclear deterrence, trade exchanges with these actors is historically acceptable.

North Korea’s desire to become part of the inter-dependent capitalist world is unquestioned. But it needs to choose whom it wants to dependent on while minimizing the chance of submitting four ultimate political goals. Benjamin Habib (2011) segmented the DPRK post-1990s economy into five parallel economies: The formal economy, the military economy, the illicit economy, the court economy, and the entrepreneurial black market (also see Haggard and Noland 2008). Like seeking socialist countries for foreign aid and assistance during Cold War time, China has replaced Russia becoming the overwhelming trade partner of North Korea. The trade volume of Sino-DPRK special economic zones remains 88 to 96 percent of Pyongyang’s total foreign trade since 2011 according to Korea Statistical Information Service. Trade was disrupted by Kim’s domestic pandemic policies, but a rapid recovery is expected due to imminent food and energy shortages in Pyongyang.

Military interests have permeated all social development strategy and the economy, especially after Kim Jong-il’s Songun (or Military-first) policy. The nuclear programme is essential for the leader to consolidate his power by ‘opening up alternative revenue’ in the military and court economies that are inhabited by key institutions and individuals. Pyongyang’s nuclear technology and scientists have historically generated revenue for the regime through illicit nuclear technology and knowhow cooperation with Iran and Syria in exchange for oil for stockpiling (Office of the DNI 2008; Park 2012). Pyongyang’s oil stockpiles have grown as a result of US-led efforts to pressure Tehran to resume nuclear talks. Nuclear-cooperation is consistent with its active defence strategy, to cooperate with ‘rogue’ nations is valid. Closer trade ties with Russia would not be a surprise after the Ukrainian War, as Pyongyang’s legitimate trading partners are sharing a fate isolation of being isolated by the West.

North Korea’s corporate ties with Southeast Asian countries is also significant – the annual trade valued at circa 18 million in 2017 (Boydston 2017). Most partners in the region are from the former socialist camp and NAM with whom North Korea has historically maintained strong diplomatic relations (North Korea in the World data). There is no paucity of literature on how North Korea does business in Southeast Asian countries (Boydston 2017; Park 2016); how the region became a major haven for North Korean overseas workers who further expand its financial networks (Lee 2016; Lee and Oh 2017); and how the UN economic sanctions have made this business model even stronger and more lucrative (Park 2016). Apart from geographical proximity and historical diplomatic ties, Southeast Asian countries share common strategic thinking with Pyongyang. Since the early-1990s, Southeast Asian countries have entertained ‘profoundly ambivalent feelings’ towards China vis-a-vis their security interests; China having ‘actively sought to influence the shaping of the new regional order’ has driven them to a tactical ‘hedging’ strategy between the US and China (Goh 2007/08, 113-114). Hedging is an up-to-date independent global response to the impetus of great power domination. Obstacles remain as Southeast Asian actors do not favour a proliferation of nuclear weapons in the region (Liang 2021) and relations with DPRK were once setback in 2017 following the political assassination of Kim Jong-nam in Malaysia (Kottasova 2017). As the dual regional security role that China and US are playing became clear, Southeast Asia was considered an optimal diplomatic and trading ‘entrepôt’ for Pyongyang in steering through uncompromising security divergencies with great powers while remaining true to its Juche course.

North Korea as an international system adapter

North Korea adapts to the international system in its own way. Its role in the international strategic system is based on the shape of its contemporary strategic thinking. The strategic culture of Juche incorporates respect for national independence; complete equality with other nation-states; non-interference in Korean internal affairs; and opposition to all manner of domination. Political sovereignty is the highest principal in North Korea’s foreign policy. The challenge for great powers to engage Pyongyang arises from the latter’s unique security perceptions that derives from its security central paradigm and strategic preferences. The sovereign country contains the goals and values that the leaders of North Korea are always ready to promote and defend.

Its desire of survival and prosperity do not differ from any other state actors in the international system. Its unique pride determines a set of priorities that the society and the leader are not prepared or willing to be negotiable. North Korea’s pride, as the Cold War historical resources agreed, has long association with its unrealistic anti-domination spirit, its entangled but desired relations with all great powers, and its political autonomy particularly in comparison with the Southern Korean governments. This feeling of pride has been injected in North Korean leader’s mind before the founding of the nation-state, and the subsequent world events, interacted through the lens of Juche, only being fuelled and refuelled to infinity. China’s rise and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in confronting the “hegemonic US” seemed to accede to a more friendly regional and global power structure to Pyongyang. The continuities of its strategic culture since 1945 and return of the ideology under the recent security environment would suggest Pyongyang’s national interests in encouraging the “revolutionary frontline” of its perceived anti-American and anti-imperialist movements, seeking to position South Korea uncomfortably amidst great power competition, while engaging in bilateral interactions with all major powers.

Figures

References

An, T. S. (1983) North Korea in Transition From Dictatorship to Dynasty, London: Greenwood Press.

Axelrod, R. (1976) ‘The cognitive mapping approach to decision making’, in R. Axelrod (ed.), Structure of Decision, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Booth, K. (1979). Strategy and Ethnocentrism. London: Croom Helm.

Boydston, K. (2017) ‘North Korea and the Southeast Asia connection’, Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 26.

Cha, V. (2012) The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future. London: The Bodley Head.

Chandran, N. (2017) ‘China isn’t the only country propping up North Korea’, CNBC, May 23.

Choe, J. C. and Won C. G. (2014) Korea’s Division and Its Truth, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, G. C. (1997) Bukhan Juche Sasang e kwanhan Yeonggu [A Study of North Korean Juche Ideology], Seoul: Sohyangkak.

Cummings, B. (1974) ‘Kim’s Korean communism’, Problems of Communism, 23(3), 34-36.

Farrell, T. (2002). Constructivist Security Studies: Portrait of a Research Program. USA and UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Goh, E. (2007/08) ‘Great powers and hierarchical order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing regional security strategies’, International Security, 32(3), 113-157.

Gray, C. S. (1981) ‘National style in strategy: The American example’, International Security, 6(2), 21-47.

Habib, B. (2011) ‘North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme and the maintenance of the Songun system’, The Pacific Review, 24(1), 43-64.

Haggard, S. and Noland, M. (2008) ‘North Korea’s foreign economic relations’, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 8(2), 219-246.

Hershberg, J. G. (1995) Cold War International Project History Project Bulletin No.6/7, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/bulletin-no-67-winter-1995 (accessed March 1, 2019)

International Institute for Strategic Study (2016) The Military Balance 2016. London, United Kingdom: Europa Publication Ltd.

Johnston, A. I. (1995a) ‘Thinking about strategic culture’, International Security,19(4), 32-64.

Johnston, A. I. (1995b) Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Johnston, A. I. (1996) ‘Cultural realism and strategy in Maoist China’, in P.J. Katzenstein (ed.), The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics, New York: Columbia University Press, 216-270.

Jon, C. N. (2000) A Dual of Reason Between Korea and US, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Katzenstein, P. J. (1996) New Directions in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kihl, Y. W. (n.d.) ‘Unification policies and strategies of North and South Korea’, International Journal of Korean Studies, 231-244.

KCNA (2013) ‘Law on Consolidating Position of Nuclear Weapons State Adopted’, April 1.

KCNA (2021a) ‘Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Makes Opening Speech at 8th WPK Congress’, January 6.

KCNA (2021b) ‘WPK General Secretary Kim Jong Un Makes Concluding Speech at Eighth Congress of WPK’, January 13.

KCNA (2021c) ‘Our honorable Chairman Kim Jong-un has given a historic administrative speech On Our Struggle Toward a New Development of a Socialist Society’, Sept 31.

KCNA (2021d) ‘Defense Development Exhibition Self-Defense 2021 Opens in Splendour, Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Marks Commemorative Speech at Opening Ceremony’, October 11.

KCNA (2022) ‘Let Us Strive for Our Great State’s Prosperity and Development and Our People’s Wellbeing: Report on 4th Plenary Meeting of 8th CC, WPK’, January 1.

Kim, I. S. (1955) Every Effort for the Country’s unification and Independence and for Socialist Construction in the Northern Half of the Republic, Pyongyang: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1958) Report at the Tenth Anniversary Celebration of the Founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Pyongyang: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1965a) On the Immediate Tasks of the People’s Power in Socialist Construction, Pyongyang: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1965b) For the Future Development of Light Industry, Pyongyang: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1970) The present situation and the tasks of our Party, Report at the conference of the Workers’ Party of Korea, October 5, 1966, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1971) Revolution and Socialist Construction in Korea, New York: International Publishers.

Kim, I. S. (1974) ‘For the establishment of a United Party of the working masses’, Report to the Inaugural Congress of the Workers’ Party of North Korea, August 29, 1946, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1975a) ‘Reply to the Letter of the President of the Korean Affairs Institute in Washington, January 8, 1965’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 191-201.

Kim, I. S. (1975b) ‘On socialist construction in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the South Korean revolution, Lecture at the ‘Ali Archam’ Academy of Social Sciences of Indonesia April 14, 1965’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 202-251.

Kim, I. S. (1975c) ‘On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of The Workers’ Party of Korea, Report delivered at the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea, October 10, 1965’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 291-331.

Kim, I. S. (1975d) ‘On the elimination of formalism and bureaucracy in Party work and the revolutionization of functionaries, Speech to functionaries of the departments of organizational leadership and propaganda and agitation, Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, October 18, 1966’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 421-458.

Kim, I. S. (1975e) ‘Let us intensify the anti-imperialist, anti-US struggle, Article published in the inaugural issue of the theoretical magazine Tricontinental, organ of the organization of solidarity of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, August 12, 1967’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 538-545.

Kim, I. S. (1975f) ‘Let us Embody The Revolutionary Spirit of Independence, Self-Sustenance and Self-Defence More Thoroughly in All Fields of State Activity, Political programme of the Government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea announced at the first session of the fourth Supreme People’s Assembly of the DPRK, December 16, 1967’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 4, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 546-610.

Kim, I. S. (1976a) ‘On the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Korean People’s Army, Speech at a banquet given in honour of the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Heroic People’s Army, February 8, 1968’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 5, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 1-10.

Kim, I. S. (1976b) ‘The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is the banner of freedom and independence for our people and a powerful weapon for building socialism and communism, Report at the 20th anniversary celebration of the founding of the DPRK, September 7, 1968’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 5, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 130-199.

Kim, I. S. (1976c) ‘Some problems of manpower administration, Concluding speech at the 18th enlarged plenary meeting of the fourth Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, November 16, 1968’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 5, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 276-293.

Kim, I. S. (1976d) ‘Report to the fifth Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea on the work of the Central Committee, November 2, 1970’, in Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 5, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House, 408-526.

Kim, I. S. (1976e) Answers to Questions Raised by Foreign Journalists, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1976f) ‘Report on the Work of the Central Committee to the Fourth Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea, September 11, 1961’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 3, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 57-204.

Kim, I. S. (1976g) ‘Our people’s army is an army of the working class, an army of the revolution; Class and political education should be continuously strengthened, speech delivered to People’s Army unit cadres above the level of Deputy Regimental Commander for political affairs and the functionaries of the Party and the Government organs of the locality, February 8, 1963’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 3, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 465-525.

Kim, I. S. (1978a) ‘Let us promote the building of socialism by vigorously carrying out the three revolutions, Speech at the meeting of active industrial workers, March 3, 1975’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 144-182.

Kim, I. S. (1978b) ‘On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea, Report delivered at the commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the foundation of the Workers’ Party of Korea, October 9, 1975’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 197-232.

Kim, I. S. (1978c) ‘The Non-Alignment Movement is a mighty anti-imperialist revolutionary force of our times, Treatise published in the inaugural issue of the Argentine magazine, ‘Guidebook to the Third World’, December 16, 1975’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 233-237.

Kim, I. S. (1978d) ‘Talk with the Chief Editor of the Japanese political magazine Sekai, March 28 1976’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 238-258.

Kim, I. S. (1978e) ‘Theses on Socialist education, Published at the 14th Plenary Meeting of the fifth Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, September 5, 1977’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 344-392.

Kim, I. S. (1978f) ‘Let us build up the strength of the people’s army through effective political work, Speech at the Seventh Congress of Agitators of the Korean People’s Army, November 30, 1977’, Kim Il Sung: Selected Works vol. 7, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers, 393-413.

Kim, I. S. (1982a) On the Juche Idea, Treatise Sent to the National Seminar on the Juche Idea Held to Mark the 70th Birthday of the Great Leader Comrade Kim Il Sung, March 31, 1982, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I.S. (1982b) The Guiding Principles of the Juche Idea, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1982c) ‘Let’s sincerely study military’, Dialogue with Students from Kim Il Sung University, August 17, 1962, Pyongyang: The Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1989) On Further Improving The Standard of Living of The People, Speech at a Consultative Meeting of Senior Officials of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, February 16, 1984, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1990) On the five-point policy for national reunification, Speech at an enlarged meeting of the Political Committee of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, June 25, 1973, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1991a) For A Free and Peaceful New World, Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the 85th Inter-Parliamentary Conference, April 29, 1991, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim I. S. (1991b) Kim Il Sung Selected Works, vol. 1, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, I. S. (1992) With the Century, from April 1912 to August 1945, Pyongyang: Korea Labor Publishers.

Kim, I. S. (1993) Ten-Point Programme of the Great Unity of the Whole Nation, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim I. S. (1995) For The Development of the Non-Aligned Movement, Pyongyang: Foreign Language Publishing House, 117-144.

Kim, I. S. (2008) ‘On eliminating dogmatism and formalism and establishing Juche in ideological work’, Speech to Party Propagandists and Agitators, December 28, 1955, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim, Y. C. (1973) Foreign Policies of Korea, Washington D.C.: Institute for Asian Studies.

Kottasova, I. (2017) ‘North Korea cut off by 3rd biggest trading partner’, CNN Money, May 1.

Krishnan, R. R. (1981) ‘North Korea and the Non-Aligned Movement’, International Studies 20 (1-2), 299-313.

Lankov, A. (2005) Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Lankov, A. (2013) The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. US: Oxford University Press.

Lee, C. M. (2004) ‘Rethinking future paths on the Korean Peninsula’, The Pacific Review 17(2), 249-270.

Lee, S. S. and Oh, K. S. (2017) Study on the Actual Condition of Overseas Workers in North Korea, Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification.

Lee, Y. H. (2016) ‘Current State and Outlook on North Korea’s Policy on Labor Dispatch Abroad’, Studies on International Trade 21(4), 111-138.

Liang, T. N. (2021) ‘North Korea’s dwindling relations with Southeast Asia’, East Asia Forum, April 24.

Macmillan, A., Booth, K. and Trood, R. (1999) ‘Strategic culture, in K. Booth and R. Trood (eds.), Strategic Cultures in the Asia-Pacific Region, US: St. Martin’s Press.

McInnis, K. (2022) ‘Integrated Deterrence’ Is Not So Bad, Washington: Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Office of the DNI (2008) ‘Background Briefing with Senior U.S. Officials on Syria’s Covert Nuclear Reactor and North Korea’s Involvement’, April 24.

Ostermann, C. F. and Person, J. (n.d.) Crisis and Confrontation on the Korean Peninsula, 1968-1969, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/crisis-and-confrontation-the-korean-peninsula-1968-1969-0

Park, J. S. (2012) ‘The Leap Ballistic Missile Program: The Iran Factor’, NBR Analysis Brief.

Park, J. (2017) ‘Restricting North Korea’s Access to Finance’, Statement before the House Committee on Financial Services Subcommittee on Monetary Policy and Trade, July 19.

Person, J. (n.d.) After Détente: The Korean Peninsula, 1973-1976, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/after-detente-the-korean-peninsula-1973-1976

Radchenko, S. and Szalontai, B. (n.d.) North Korea’s Efforts to Acquire Nuclear Technology and Nuclear Weapons: Evidence from Russian and Hungarian Archives, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/north-koreas-efforts-to-acquire-nuclear-technology-and-nuclear-weapons-evidence-russian

Ri, J. C. (2012) Songun Politics in Korea, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Rodong Sinmun (1977) ‘The Idea of Juche and The Worker’s Party of Korea’ September 18.

Rodong Sinmun (2019) ‘DPRK FM Spokesperson Fully Supports Stand and Measures of Chinese Party and Government towards Hong Kong Issue’, August 11.

Rodong Sinmun (2020) ‘Statement of Spokesman for International Department of C.C., WPK’, June 4.

Rodong Sinmun (2021) ‘Great Programme for Struggle Leading Korean-style Socialist Construction to Fresh Victory on Report Made by Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un at Eighth Congress of WPK’, January 10.

Scalapino, R. A. and Lee, C. S. (1972) Communism in Korea: The Movement, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Sigal, L. V. (1997) ‘The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Understanding the Failure of the ‘Crime-and-Punishment’ Strategy’, Arms Control Association 1 May, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/1997_05/sigal (accessed December 26, 2017).

Snyder, J. L. (1990) ‘The concept of strategic culture: Caveat emptor’, in C.G. Jacobsen (ed.), Strategic Power: USA/USSR, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 3-9.

Solingen, E. (2007) ‘North Korea’, Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia & the Middle East, 118-40. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Suh, D. S. (1988) Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader, New York: Columbia University.

Taylor, M. (2015) ‘Only a disciplined people can build a nation’: North Korean mass Games and Third Worldism in Guyana, 1980-1992’, The Asia-Pacific Journal 13(4), 1-25.

Vu, K. (2021) ‘The ups and downs of the Vietnam-North Korea relationship’, Interpreter, Sydney: Lowy Institute, February 24. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/ups-downs-vietnam-north-korea-relationship (accessed February 24, 2021)

Waltz, K. (1979) Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Wang, C. and McGregor, R. (2019) ‘Four reasons why China supports North Korea’, Interpreter, Sydney: Lowy Institute, March 4. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/four-reasons-why-china-supports-north-korea (accessed March 4, 2019)

Wendt, A. (1995) ‘Constructing International Politics’, International Security, 20(1), 71-81.

Woodward, B. (2020) Rage. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Yim, Y. S. (1983) ‘Maoism and North Korean strategic doctrine’, The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 3(2), 335-355.

Further Reading on E-International Relations