The middle of May and the hills inland from Italy’s Adriatic coast witness a bolt from the blue, a blast from the past. Julian Alaphilippe rolls into Fano alone to raise his arms as the winner of stage 12 of the Giro d’Italia. It’s only his fifth victory in the past two-and-a-half years and comfortably the biggest in that time. But more than anything, it’s the manner of it: audacious, swashbuckling, and rippled with emotional energy that makes it so much more than the sum of the watts.

Taking flight from a large, high-calibre and only-recently-formed breakaway with 120km still to ride should have been a suicide mission, even in the company of the Italian Mirco Maestri. But Alaphilippe has taken an impossible set of chords and somehow set them to his own unique rhythm. Maestri’s reaction says it all. In some ways, he’s a willing accomplice in his own downfall, left behind on the final climb, but he knows he has been part of something special. “I want to be a bee,” he writes philosophically on Instagram. “Bees are not designed to fly, but bees do not know physics and fly anyway. Today, in my own way, I tried to be one.”

It’s a rather romantic vision, one that seems increasingly difficult to cling to in the scientifically-charged modern era of the sport.

“Pure cycling,” Alaphilippe calls it.

This is the Alaphilippe who won two world titles in two years. This is the Alaphilippe who won six Tour de France stages, Milan-San Remo, and Strade Bianche. This is the Alaphilippe who would have you on the edge of your seat, if not jumping out of it.

After 30 months in the darkness, he has set the cycling world alight again.

The question is, what happens now? Will the lights stay on, or was that just a momentary flicker?

Two years is a long time in today’s hyper-accelerated world of pro cycling, and Leuven 2021, the scene of Alaphilippe’s second world title and arguably his greatest-ever performance, feels like a lifetime ago. Since then, the Frenchman has struggled badly, the souplesse and panache replaced by a more laboured pedal stroke, a more muted demeanour. He has been battered from side to side, his ribs and collarbones taking heavy blows at the same time as his morale has been pummelled by his own boss.

All this goes a long way to explaining his slump in results (all things being relative), but does it go the whole way? There have been suggestions that a more general, irreversible decline has set in. There’s been talk of an exit from QuickStep plus links to TotalEnergies, somewhat ominous given the French second-division team have in recent years splashed out on Niki Terpstra and Peter Sagan in what turned out to be barren twilights to glittering careers. The parallel with Sagan is striking, a fellow multiple world champion who was fading, then suddenly produced one of his career’s greatest hits with a Giro d’Italia stage win, only to fade further.

“I was never dead,” Alaphilippe quipped after that Giro victory, insisting that rumours of his demise had been greatly exaggerated.

His coach and cousin, Franck Alaphilippe, agrees, even if he does acknowledge some wear of parts due to age.

“The main thing is that when he suffers an injury or illness, the period of convalescence is much longer than it used to be,” Franck tells Cyclingnews.

“If he’d encountered the difficulties he’s had the past two years at the age of 20, he’d have bound back much quicker each time. His body doesn’t react in the same way now; the path back to his top level is longer.”

Wearing the world champion’s jersey for a second season, Alaphilippe’s 2022 campaign was a write-off. After illness had hampered his winter preparations, a crash at Liège-Bastogne-Liège left him with a broken shoulder blade, ribs, and a collapsed lung, eventually ruling him out of the Tour de France. His comeback was knocked by COVID-19, and he then crashed out of the Vuelta a España with a dislocated shoulder. 2023 was less dramatically littered with bad luck, and it even featured a couple of decent wins, but he never found the sort of momentum that would propel him back to his old self.

However, putting together a consistent late-season, off-season, and early-season has enabled him to move through the gears.

“His physical numbers are as good as ever, and they’ve got better over time, notably already at the end of last season,” says Franck. “Not having those problems is key. This is, let’s say, the first season in more than two years where he’s had a really good winter under his belt.

“His condition has been on the up the whole time, and the proof of that comes at the Giro—that really gave him a boost in morale when it came to preparing for the second half of the season.”

A boost in morale was most welcome, but Franck insists Julian never allowed his head to drop completely. For someone who places such a premium on enjoying himself and expressing himself on the bike, that wasn’t always a given.

“In spite of everything, it’s his mentality that has never been diminished, and happily so, because if it had, I think he’d have stopped [his career],” Franck says.

“Each time, he had to pick himself up and start again from zero. He struggled to complete routine training blocks. So, for sure, it was a tough time. But he never threw in the towel. Each time he got back to work, set himself new objectives, trusted that he would get back to the top.”

The soul of the Blues

The jury may still be out on whether Alaphilippe is definitively ‘back’, but we might well know more in a couple of weeks’ time. You could hardly set a more perfect scene for an Alaphilippe virtuoso than the Olympic Games road race on August 3.

The French jersey on his back, French roads underneath his tyres, a one-day winner-takes-all event, the biggest sporting occasion in the world, an achingly long route, a series of punchy climbs, small teams, no race radio… A recipe, if ever there was one, for pure cycling.

“It will be spectacular, whatever happens,” Alaphilippe confirmed recently. “It’s another dimension to what we’re used to all season. I’ll try to get there as strong as possible, wide-eyed and full of motivation.”

Alaphilippe has unfinished business with the Olympics. He made the decision to skip the previous Games in Tokyo in 2021 partly due to the birth of his first child, so you have to go back to Rio in 2016 for his only appearance and a strong sense of ‘what might have been’. A 24-year-old third-year pro who was already making big splashes, he was well in the medal mix when he crashed on the late descent of Vista Chinesa. He rolled across the line in fourth place, 22 seconds down on the winning group, a little proud but mostly rueful.

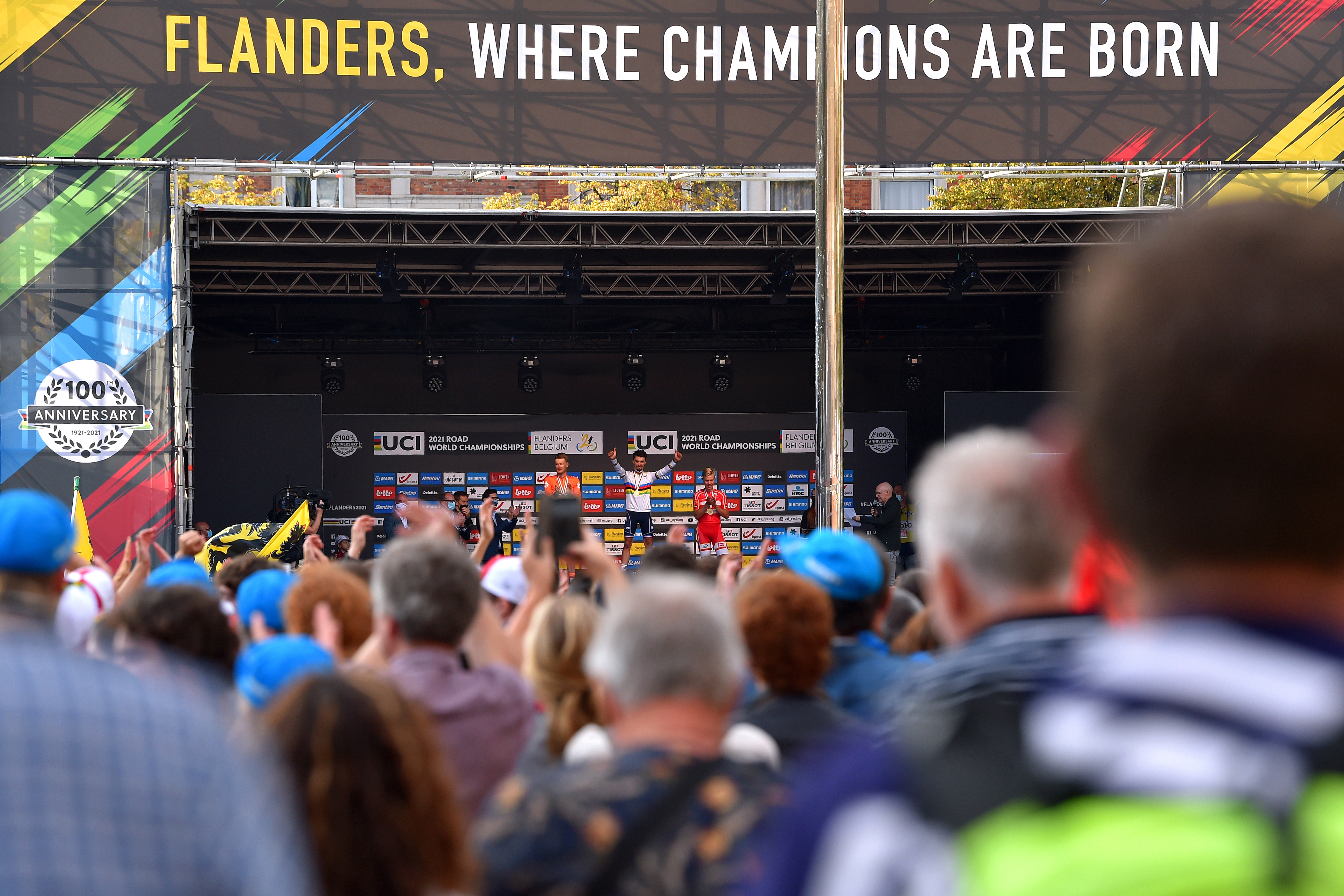

Since then, of course, Alaphilippe has won two world titles in French colours, the first in Imola, Italy, in the pandemic year 2020 and backed up by a surprise triumph in Leuven, Belgium, in 2021—justification enough for passing on Tokyo.

Thomas Voeckler, the French national selector, has described Alaphilippe as ‘L’âme des Bleus’ – the soul of the Blues, as French national sides are known. In what was a very competitive French fight for just four places, he hinted that Alaphilippe might not have made the cut earlier in the year and claimed it wasn’t a done deal even after the Giro. But you sense Voeckler, himself one of the peloton’s more expressive and emotional figures back in the day, wouldn’t have left his talisman at home.

“They already appreciated each other a lot when their careers crossed over in the peloton, then when he became the national coach their relationship strengthened even more,” says Franck Alaphilippe. “There’s trust, above all. Thomas has faith in Julian and Julian has faith in Thomas.”

The reason Leuven was such a surprise was that Alaphilippe admitted that on some level he didn’t really want to win; that the rainbow jersey had weighed heavily and he was actually looking forward to removing it from his shoulders. And yet he got so wrapped up in the race that he went and won it with an electrifying solo final lap. When you have a rider who can pull something like that out of nowhere, you can’t not take them.

This time, however, Alaphilippe is hungrier than ever.

“He’s truly going all-out for this one,” says his cousin and coach. “He has strong memories of Rio, and although there was a period where the Olympics weren’t a priority for him – that was the Tour de France – he’s aware he might never get the chance to compete in them again. He wants to make the most of it.

“He loves riding for France. When he has the jersey of the French team he is always super motivated. I don’t mean to say that’s not the case with a QuickStep jersey, but he has always had good times with that French jersey. On top of all that, it’s an Olympics in Paris, which only makes it more special for him.”

In the French capital, Alaphilippe will find a course to his liking, first of all with a long distance of 273km and then with a glut of punchy climbs, notably the 1km hike to the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre on the finishing circuit. The climbs may be a shade short of steepness and length to suit him to perfection, but then there’s more elevation gain than there was in Leuven. Besides, with no nation boasting more than four riders and with race radios banned, it’ll be the sort of heavy metal chaos Alaphilippe seems to relish so much.

While the lion’s share of his rivals will be travelling to Paris from Nice after the Tour de France, Alaphilippe will be coming in from the Czech Republic, where he is finishing his fine-tuning after a long altitude training camp in Italy.

“He’s doing the opposite to most of the other favourites. He won’t have that same workload in the legs as the Tour de France guys, but we’re playing heavily on freshness,” says Franck Alaphilippe.

“You can almost compare it to the World Championships in Leuven,” he adds. “The fact that he did the whole Giro gave him a really good base on a physical level. Now with a good altitude camp in the legs, plus some racing to get the system firing, we are confident he will arrive in Paris in good shape.”

After that, the sense of occasion will do the rest: “The adrenaline that you get with a major international championship, Julian thrives off that.”

Lou Lou is racing in the moment

Whatever happens in Paris, Alaphilippe says the Olympics will have no bearing on his future. But that question mark over his career trajectory will linger, not to mention the more pressing concern of where he’s actually going to race next season.

Out of contract at the end of the year, Alaphilippe’s future at QuickStep, where he started his career a decade ago, has appeared shaky amid the steady flow of barbs from the team’s manager, Patrick Lefevere. The veteran Belgian will never miss an opportunity to grumble about the amount of money he has to pay his top riders and will use this as justification to call them out at the first sign of results drying up.

Lefevere has been chipping away at Alaphilippe for the best part of three years, but things boiled over earlier this year when he accused Alaphilippe of unprofessionalism – “too much partying, too much alcohol” – and even brought Alaphilippe’s partner, the Tour de France Femmes director, Marion Rousse into the firing line – “he’s seriously under her influence, maybe too much”. Rousse hit back with a public statement urging Lefevere to “show a little respect… and class”.

It was widely assumed that that was the relationship damaged beyond repair, although Alaphilippe has suggested he’d be open to a new deal. Either way, he’s on the market still for 2025, and while his value will certainly have dropped in comparison to a few years ago, the blast from the past at the Giro might have pushed it back out again, no doubt to Lefevere’s chagrin. The Olympics might just do the same.

“Honestly, I’m not thinking about that. My future is not going to rest on the Olympic Games. I don’t think so,” Alaphilippe responded when the subject was raised at a press conference announcing France’s line-up.

“It’s a big personal objective for me, that’s for sure, but going into the Games, I’m not thinking about the end of the season or next year. I’m thinking about the race and giving everything for France. If there are teams interested in having me with them next year, it’s not the Olympics that are going to change things. Winning a medal would be magnificent, but it would have nothing to do with my future.”

Alaphilippe was talking about his immediate future, but also his longer-term future. His cousin has already mentioned the fear of him packing it all in, and at 32 Alaphilippe is already talking like the end is not too far away.

“Concerning what’s next and the end of my career, that’s another matter, and I’m not going to take the start of the Olympics thinking about it,” said Alaphilippe not dodging the question but instead labouring the points. “I really want to separate the two things. They don’t have anything to do with each other.”

No distractions; the Olympics will be raced in the moment.

Setbacks may have crept in more often than he’d have liked, bouncing back might take a little longer with each passing year, but Alaphilippe still feels capable of rising to these moments. “I’ve learned the value of patience now,” he said ahead of this season. “I still have the same desire as before, but I’m more patient.”

That’s the thing about racing on emotion, anyway. You can’t simply conjure these things at will. Alaphilippe is a keen musician, and there has always been an element of improvisation to his greatest hits, of an energy building into its own unstoppable force. The big exploits may now be fewer and farther between, but in a way that only enhances their impact.

Really, though, Alaphilippe knew all this already. In the glow of his second rainbow jersey in Leuven, he issued what amounted to a proclamation of his cycling philosophy, and it’s almost more relevant today than it was back then.

“Since 2014, I’m still the same rider, and I don’t want to change anything. I took a lot of pleasure in riding like this, and for me, it’s really important to keep this pleasure because cycling is a hard sport, and I don’t want to become a robot. I want to continue to attack, to enjoy, to race with panache – even if I lose sometimes or a lot of times. I want to give everything to try and win, with my heart.”

In other words: pure cycling.