You’ve been at the top of the sport for more than a decade,” I begin softly, aiming to warm Romain Bardet to my theme before coaxing him to reflect on his long career at the sharp end. So I’m shocked to get knocked back so soon. “At the top?” he interrupts, taking issue with my premise. His longevity at the top is objectively true: he’s a two-time podium finisher at the Tour de France and runner-up at this year’s Liège-Bastogne- Liège – but he has a point to make about the fact he hasn’t won any of cycling’s biggest races. “The most organised team or best riders win almost every race they target and it means the sport has become less entertaining,” he says. “Nowadays, you can bet that the next three Grand Tours will be won by the same one or two teams.”

I’m speaking to Bardet at his winter training camp in January, but fast- forward to May and his point has a particular resonance: at the time of writing, Tadej Pogačar of UAE-Team Emirates is sitting pretty at the top of the Giro d’Italia’s GC standings. I’d intended to focus on the Frenchman’s 2024 season before possibly broaching the subject of whether he’s considering retirement – but his interjection has thrown my plans out of the proverbial window. I sense that the 33-year-old, who alongside Julian Alaphilippe and Thibaut Pinot has sustained the glow in the embers of French cycling, is in pensive mood.

I probe a little deeper. “Is cycling in a better position than 10 years ago?” I ask, slightly leadingly. “What do you mean?” he answers. “Can we trust the sport?” I spell it out. Sitting opposite me, his legs crossed in a formal, slightly defensive manner, he takes a swig of water. “OK, I know what you mean. It’s a hard question,” he pauses, and I fill the silence by reassuring him that he doesn’t have to respond if he’s uncomfortable with the question. “No,” he cuts across me, “I do feel comfortable.”

Within a few minutes I realise that he is not just comfortable and willing to speak openly and directly; he has a lot to get off his chest. In fact, it becomes clear that Bardet is itching to share his manifesto for the sport, an agenda that he might just be the man to steer into action after he retires – with the core objective being to make cycling more competitive, entertaining and trustworthy. “I want to stay in cycling to really have a positive impact on the future,” he begins, “and this is why I have some projects, but they will take time to really take shape.”

Predictable podiums

Romain Bardet is a respected savant of the sport, at least in his native France. He chooses his words with precision, and holds forth with brio. When he speaks, the French cycling fraternity listens – and perhaps the rest of us should, too. Hailing from the town of Brioude in the Auvergne-Rhône- Alpes region of south-central France, this bard of Brioude has been competing at the top of the sport for 13 seasons; he has finished second and third overall at the Tour de France, and won three stages and the King of the Mountains jersey in his home Grand Tour. He has also come close to winning Monuments, WorldTour stage races, and even the World Championships in 2018.

Though he has had an enviable and consistent career, the DSM-Firmenich- PostNL rider is perhaps known as a perpetual ‘nearly man’. As this issue goes to press, he is sitting sixth overall at the Giro, and is next month set to return to the Tour de France for an 11th time. But it may well be a farewell lap. Looming retirement, though, hasn’t dimmed his love of the sport.

Quite the opposite, it seems. When he remembers his breakthrough years with AG2R La Mondiale, he recalls a more level, fairer field of play, which he wants to see reinstated. “Looking back at the 2014 Tour [where he finished sixth, aged 23], I felt like it was much more open, and it was easier to access the top if you were a good rider with good commitment in a small team,” he says. And today? “There is a good chance that guys from the same two teams will make up the podium or top-five, and I find that a bit less interesting.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Money, more of it these days coming from billionaires or nation states, is a large factor behind the era of superteams, Bardet says, because it “makes them powerful and they can afford to have more leaders”. He describes a situation where several riders with GC potential ability are now heaped together onto the same two or three teams working for superstar leaders. “You can have a rider with the power profile [of a GC contender], but he couldn’t go to a lower- ranked team and say he’s going to win the Giro or the Vuelta a España. It wouldn’t happen. So right now we have a lot of riders who would, in other teams, be leaders, working for the best guys on the planet. Where is the competition?”

Is there a solution? “A salary cap,” he insists. “People say when big sponsors are keen to invest the money, we shouldn’t introduce a cap, but it works pretty well for the competition in French rugby. If we had a salary cap or a draft [as is common in US sports], we would be able to distribute the best riders more fairly across the 18 WorldTour teams.” Bardet is not alone in this belief: French teams and riders have long since argued for the introduction of a salary and/or budget cap. Many have dismissed this call as sour grapes, the French looking for an excuse to explain their decades-long fall from the sport’s greatest heights. Interestingly, though, the idea is now being raised beyond France by influential figures including Jayco-Alula’s general manager Brent Copeland, who is also the president of the union representing the men’s professional teams, the AIGCP.

It doesn’t end with a cap in Bardet’s vision for a fairer future. He has another proposal to prevent the same few teams from scooping all the biggest prizes. “We should go to Grand Tours with smaller teams – six riders in normal races, seven in Grand Tours [down from eight], and overall team sizes no bigger than 20-25 riders [currently teams are capped at 30 riders].” What’s his reasoning? “If you line up with fewer guys, you can bring more teams to every race, so there’d be more sponsors who can do the Tour, which means more money for all. The competition will be more open, as it will be much harder for teams to control the race.”

On the theme of controlling races, Bardet also has strong views on race radios, first introduced in the early 1990s and now ubiquitous. “We should turn them off,” he says. “When Visma and UAE want to control the start of a race, they’re always talking on their radio to their sports directors. When we ride the Worlds [where race radios are not permitted] you have to look, be aware and have a feel for the race, instead of just having your earpiece on and waiting for your command. It keeps the rider much sharper.”

The sport’s governing body, the UCI, threatened to ban radios multiple times in the early 2010s, and in 2017 its current president David Lappartient came out in favour of prohibition on grounds that radios could be hacked for race-fixing purposes. “A lot of sports directors are against [banning radios], as they say they’d lose power and impact on a race,” Bardet continues, “but I disagree because they’ll have to be smarter in their team meetings to make sure the riders are all involved to apply the strategy from the beginning. For me, it’d really help to increase the reliability and interest around bike racing, because the human being would have to show up.”

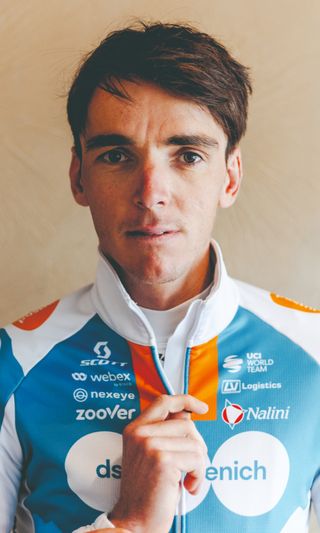

Romain Bardet has ideas to change cycling

(Image credit: Harry Talbot/Future)

The ideas examined: Bardet’s manifesto – and the counter-arguments

Implement a salary and/or budget cap

Pro: Proponents of the idea say it would stop the richest teams hovering up all the best talent, and readdress a competitive balance.

Con: Those who disagree say it would discourage investment into the sport, limiting reach and development.

Ban race radios

Pro: Pro: Banning radios would, in theory, encourage spontaneous, creative riding and prevent the strongest teams from dominating, as they would have less knowledge of what’s happening in the race. Radio-free races such as the World Championships appear to support this case.

Con: Attila Valter of Visma-Lease a Bike says: “It would all be fun and games until you lose a Grand Tour because you can’t communicate to your team car that you’ve had a crash or a puncture.”

Limit team sizes

Pro: Teams would have fewer riders to control racing, leading to more open dynamics and lower budgets.

Con: Grand Tour team sizes reduced from nine to eight not so long ago and certain teams still dominate. Critics say it would lead to fewer big teams at the smaller-ranked races, making it harder for those races to survive. It could also lead to certain riders being over-raced.

Compulsory vocational education for U23 riders

Pro: It would provide young riders with greater opportunities outside of cycling after they exit the sport, at whatever age. It would also reduce the risk of burnout.

Con: Many argue that cycling is merely belatedly following the trend of other sports in having an influx of young superstars. Providing education could also cost teams additional expense.

Too much, too young

I learn from his team that Bardet enjoyed our interview, and so I speak with him again in early May, just before he is due to start the Giro d’Italia. Th e 2024 season so far has been characterised by dominating and suff ocating displays of brilliance by Tadej Pogačar, Mathieu van der Poel and, until his crash, Jonas Vingegaard, and I’d like to get a sense of Bardet’s reaction. “On one hand, you can feel that you are part of history, racing with the biggest champions, but the sport has less suspense, and we’ve not had the feeling that something unplanned could happen,” he says. I share with Bardet a conversation I had in March with fellow long-serving pro, Kiwi George Bennett, now of Israel-Premier Tech, who lamented how nowadays “the race is for second” but anyone who says so gets accused of being “defeatist”. Bardet nods earnestly. “I feel the same. The time gaps are so big [that we are] racing for the spots down the rankings now.”

The Frenchman is keen to stress that he isn’t weary with the sport. Rather, he is speaking up for the sake of younger athletes who, like he did, are trying to turn a childhood obsession into an occupation. “I’m really, really concerned with the direction cycling is going in now with young people,” he says. “Before I joined the WorldTour at 21, cycling was not too important for me. I developed as a human, did my studies on the side, and had my social life – the three years I was at university [in Grenoble studying an MBA in business administration] were the best years of my life.” He sketches a period free from concerns about how student life would affect his cycling. “I was going to parties a bit too much so I would only train for two hours at night, and I was a bit shit at the start of the season, but it was enjoyable.” It’s a freedom not available to aspiring pros of 2024. “Now, I only see guys at 17 who are skipping everything and just sticking to cycling. They’re chasing glory early, as they have Remco [Evenepoel] and Pogačar in their minds and think they can make a living and go straight to the podium.”

The fault lies with the teams, in Bardet’s view. “We are now down the path of trying to level everyone up from such a young age and trying to give them a long-term contract. We are going to burn out a lot of guys and leave them by the side of the road at 23 or 24.” He is concerned that these riders will have no fall-back plan, having spent the previous five or six years doing nothing “except living cycling 24/7”.

I suggest that young riders could be obliged to do an apprenticeship with their team’s main sponsor to gain skills beyond cycling. “That’s one of the models I’m dreaming of trying to put in place,” he says. “How can we make some bridges between trying to also train the human and not only the athlete? Most teams now have a development team, and they should have a duty to develop the person. There is a big world out there and cycling is only a small part of it.” He pauses before referring to his own four-year-old son, Angus. “As a parent, if my son was 15 and was about to make his way into cycling, I’d be worried for him.”

Marked by Chris Froome at the 2017 Tour de France

(Image credit: Future)

Bardet’s Palmares: the best ‘nearly man’ in the business

The 33-year-old Frenchman, who rode for AGR2 La Mondiale from 2012-2020 and now rides for DSM-Firmenich PostNL, has come close to winning both Grand Tours and Monuments:

2nd, 2016 Tour de France

3rd, 2017 Tour de France

3x Tour de France stages

1st, 2022 Tour of the Alps

1x Vuelta a España stage

2nd, 2018 World Championships

2nd, 2024 Liège-Bastogne-Liège

Discouraging doping

There is, in Bardet’s mind, a second, arguably more serious consequence of riders having no back-up plan. “I’m worried that… at some point in their career, when everything isn’t going as planned, they will try to take some shortcuts,” he says. “Doping isn’t such a hot topic anymore [but] there has been a trend to part ways with some initiatives like the MPCC.” Th e MPCC stands for the Movement For Credible Cycling, a voluntary organisation set up in 2007 that binds associated teams and riders to additional anti-doping requirements. Th e project started strongly but it has steadily lost infl uence, with several teams withdrawing their membership, including LottoNL-Jumbo (now Visma- Lease a Bike) in 2015, citing concerns over the organisation’s cortisol rules. In the current Giro, only 53 riders, 30% of the field, are members of the MPCC. Of the current top-eight-ranked teams, only Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale is MPCC-affiliated.

It’s important to state that doping violations at the highest echelons of professional cycling have been consistently low in the past decade. Bardet points out doping off ences are often not exposed until decades after they took place but credits the UCI with “working hard” on detection and prevention – and yet. “We need to explain how, although we are all training the same, more or less, all spending time at altitude, how come two or three teams are so dominant.” He’s not pointing the fi nger so much as expressing genuine bafflement. “On my personal level, I am still as good [as before], but I have to admit that since Covid some guys are really going faster, and that’s a fact.”

Pushing from the front on stage six of this year’s Giro d’Italia

(Image credit: Future)

Will 2024 be Bardet’s last year in the pro peloton? He won’t be drawn. “While I am still in cycling, I want to perform at my best,” he states. What is clear is that he is already preparing the ground to enact his model for a better sporting environment, one where the human being comes fi rst, the athlete second, led by ethics that also make the sport more entertaining for all. Is he determined to change the world of cycling? “We’ll see. It’s not easy to move things on in the cycling world,” he concedes, “but I’m thinking about the future, to try to establish something sustainable. It’s not that I am angry or think everything is bad, but I am always trying to think how we can improve.”