This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The yellow school bus has remained remarkably consistent over the past century. But as a smaller share of kids ride the bus, its role is shifting.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

A Mixed Legacy

Across county and state lines, school buses are remarkably consistent. The yolky exterior color, called National School Bus Glossy Yellow, has remained the go-to shade since 1939. Buses are outfitted with a pop-out stop sign and vinyl seats, which, in my memory, tend to be ripped up and held together with strips of duct tape. Riding the yellow school bus is a tradition shared by generations of American students—but that experience is less common now than in previous decades.

In 2022, only about a third of students rode the bus to school, down from roughly 37 percent five years before, according to a Washington Post analysis of the National Household Travel Survey. More students are getting dropped off by car or driving to class—a trend that accelerated after the coronavirus pandemic began, especially among the children of college-educated parents.

Many people are nostalgic about the school bus, but its legacy—and present—is mixed. The bus was once a transformative force in American education, enabling a switch from highly local, one-room schoolhouses, Antero Garcia, an education professor at Stanford University, told me. And in the years following Brown v. Board of Education, buses became a potent symbol of desegregation. But for many kids, the bus can be a place of stress. Students may face discipline from drivers (many of whom struggle with low pay and odd working hours) or bullying from peers. Garcia also noted that it can feel like a form of punishment for bus riders to spend hours commuting each day just to get the same educational opportunities as students who can be driven by parents.

The bus is a tool that touches millions of kids’ lives every day, but on the whole, these vehicles have hardly improved over decades—even as the education system flocks to other, new technologies. Its stagnation has come about in part because administrators tend to focus on interventions that improve test scores “rather than a dusty old bus,” Garcia said. He also noted that “there’s an assumption that school buses are for working-class kids, largely kids of color.” (According to the 2017 National Household Travel Survey, 70 percent of students from low-income families ride the school bus, whereas a majority of students from non-low-income families are driven to school in a personal vehicle.)

For years, the school-bus system has struggled to recover from a severe bus-driver shortage: At the start of this past school year, there were about 192,000 drivers—a 15 percent decline from four years earlier. From 2009 to 2019, the number of bus drivers dropped by 22 percent; in that same period, the number of students enrolled in K–12 schools grew by some 1.4 million. Moreover, the school-bus system doesn’t serve all students—a 2020 study of New York City’s school-bus ridership found that Black and Hispanic K–6 students are more likely to attend schools where buses are unavailable.

Still, some school districts are making changes: Efforts to add electric buses to school fleets have gained momentum lately. Some well-meaning educators have tried taking advantage of bus time by giving students more homework—which, Garcia said, “is the last thing kids want.” He wonders if the bus could become a site of enrichment rather than tedium. What if the bus were an opportunity for peer mentoring, for example, or film classes?

The bus is a liminal site: Bus time is part of the school day, but it’s not class time. Students gather together, but they have less structure, and there’s less of a focus on academics. This freedom makes the bus worth looking at in full, as a meaningful, rich space for kids in America.

Related:

Today’s News

- The International Court of Justice, the United Nations’ top court, ruled that Israel must immediately stop its offensive in Rafah, a city in southern Gaza.

- China continued its largest military drills in more than a year around Taiwan, days after Taiwan swore in a new president who openly supports sovereignty for the nation.

- This summer’s hurricane season could be among the worst in decades, meteorologists predict.

Dispatches

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

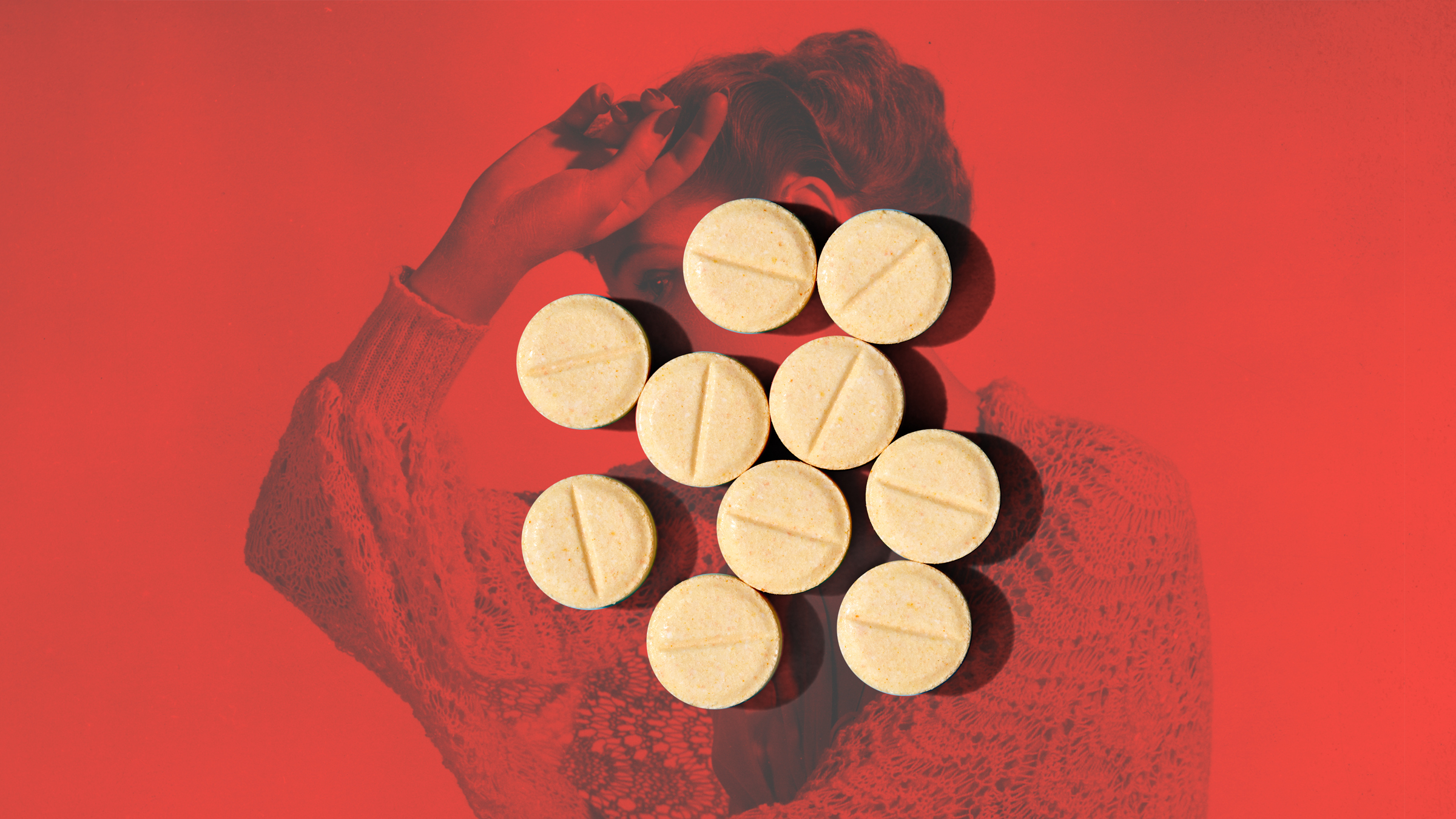

Stop Shouting Down the Women Going Off the Pill

By Christine Emba

Perhaps you’ve noticed something new at your local market. Opill, the first oral contraceptive approved by the FDA for over-the-counter use, began shipping to U.S. stores in March. It has no age restrictions and does not require a physician’s sign-off; you can now buy a three-month supply at Walmart or Target the same way you might pick up Tylenol or tampons or a six-pack of seltzer.

This is, without a doubt, a momentous development in the realm of reproductive health … Yet Opill also debuts as more and more women, in public forums and in their physicians’ offices, are raising concerns about the effects of hormonal birth control on their physical and mental well-being—and are pushing back against the idea that pharmaceuticals are their best options for trying to prevent pregnancy.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

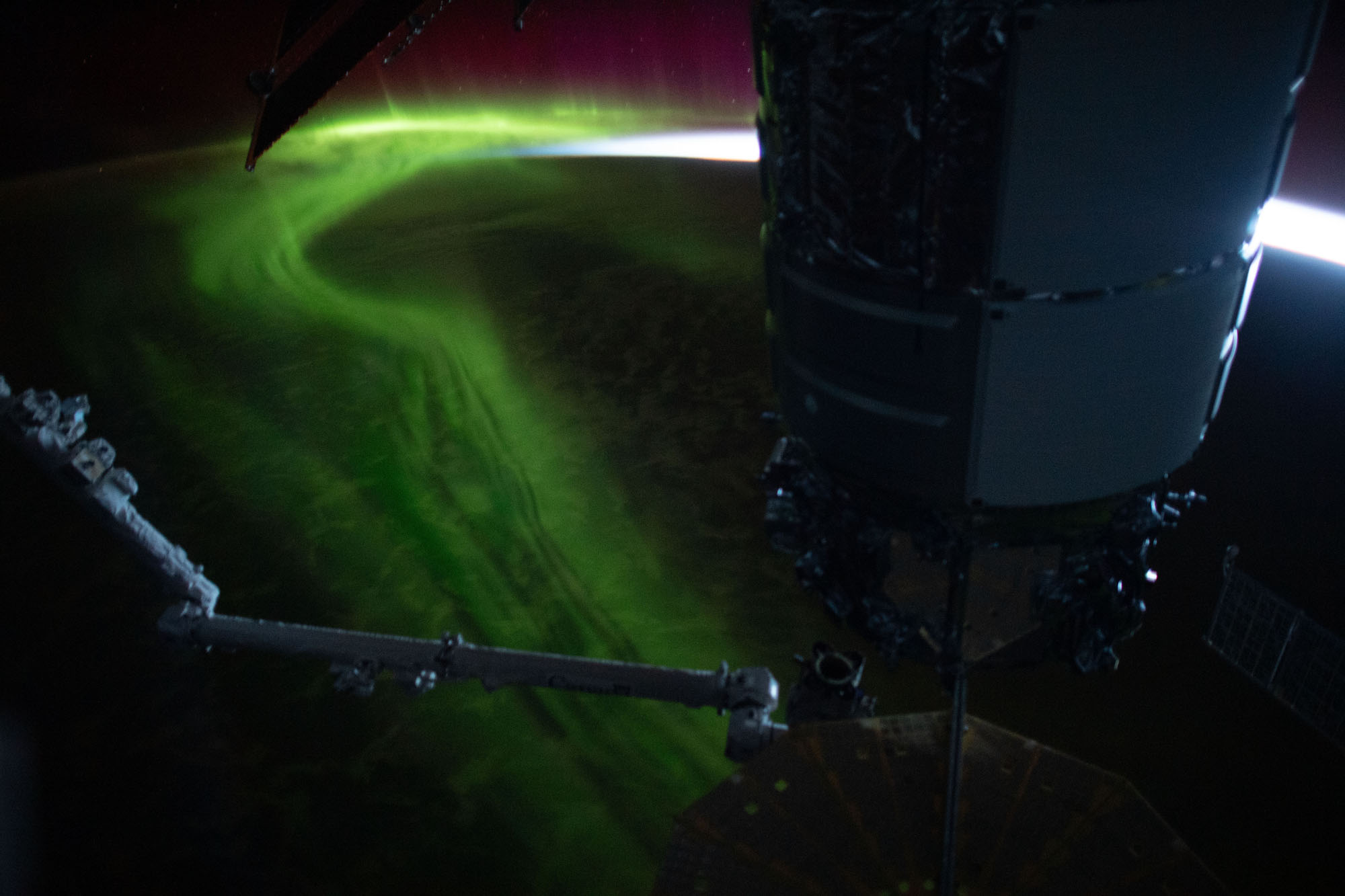

Admire. These photos of Earth from orbit, taken recently by the astronauts and cosmonauts on the International Space Station.

Read. David Shoemaker’s new book, Wisecracks, is not about comedians or jokes. Instead, he aims to illuminate the ethics of “taking the piss.”

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.